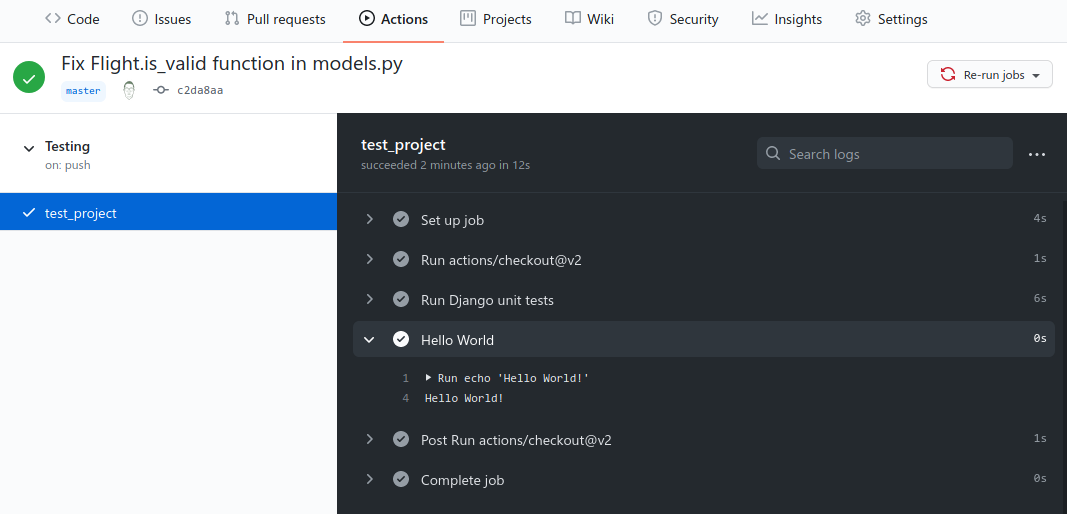

CS50's Web Programming with Python and JavaScript

Lecture 0 - Git, HTML, CSS

Git

Git is a version control system that can be used to synchronize codes between people and enable people to collaborate on the same project.

Another useful feature that Git is used for is testing and imprementing with code without losing the original.

Git can also be used to revert back older version of code. Say if we have been working on a piece of code realise that the latest version of the code isn’t working, we will need to revert to the older working version of the code.

GitHub is a website that stores Git repositories on the internet to faciliate the collaboration that Git allows for. A repo is simply a place to keep track of code and all changes to code. We can think of a repository as a centralized storage.

Some simple Git commands:

git clone <url>: Take a repo stored on a remote server (like github) and download it.git add <filename(s)>: add files to the staging area to be included in the next commit. This command tells Git that we want to add some files to be included in our next commit. This enables Git to track the file for any saved changes.git commit -m "message": take a snapshot of the repository and save it with a message about the changes.git commit -am <filename(s)> "message": add files and commit changes in one single step.git status: print what is currently going on with the repository at any given moment.git push: push any local changes (commits) to a remote server.git pull: pull any remote changes from a remote server to a local computer.git log: print a history of all the commits that have been made.git reflog: print a list of all the different references to commits.git reset --hard <commit>: reset a repository to a given commit.git reset --hard origin/master: reset the repository to its original state e.g the version that is cloned from GitHub.

When we combine different versions of code using git pull for example, a merge conflict may occur if the different versions have different data in the same location, which is like the same lines in the same file(s). Git will try to take care of the merging automatically however if two users edit the same line, a merge conflict will have to be manually resolved.

To resolve a merge conflict, simply locally remove all lines and code that are not wanted and push the reuslts.

HTML

HTML stands for HyperText MarkUp Language. It is used to lay out the structure of a web page.

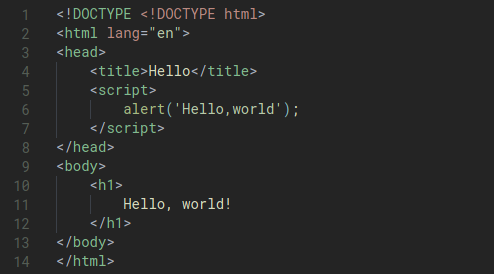

<!DOCTYPE html> is placed at the start of a HTML file to indicate to the browser that HTML5 is being used.

HTML is made up of tags. Tag generally come in pairs with data being wrapped inbetween the two tages. Tags are indented to help visualize hierarchy but any indentation is purely stylistic. Tags can also have attributes which are called data fields. Some of these attributes are optional, that simply provide addititonal information to the browser how to render the content and some can be required.

Some common HTML tags:

<html></html>: contents of website<head></head>: metadata about the page that is useful for the browser when displaying the page<title></title>: title of the page<body></body>: body of the page<h1></h1>: header (h1 is the largest header, h6 is the smallest header)<ul></ul>: unordered list<ol></ol>: ordered list<li></li>: list item (must be inside either <ul></ul>` or <ol></ol>)

<img src="path/to/img.jpg" height="200" width="300">: image stored at src attribute, which can also be a URL note that this is a single tag without an end tag both height and width are optional (if one is omitted, the browser will auto-size the image), and can also take a percentage: height=50% to automatically scale the image to a certain portion of the page<table></table>: table<th></th>: table header<tr></tr>: table row<td></td>: table data (cell)

<form></form>: form that can be filled out and submitted by the user<input type="text" placeholder="Full Name" name="name">: input field type indicates the type of data placeholder is the greyed-out text shown before the field is filled name is an identifier for the input field<button></button>: button used to submit form

Document Object Model

DOM is a way to conceptualize web pages by representing them as an interconnected hierarchy of nodes. In HTML the nodes of DOM would be the different tags and their contained data, with the <html></html> tag being at the very top of the tree. This is a very useful feature.

DOM is basically an abstract way to represent a web page HTML file as a big tree structure.

Having an understanding of DOM is helpful especially for later when we start to implement fancy things like Javascript in our web pages. It is also good for styling our webpages with CSS.

[[./images/DOM.png]]

CSS

Cascading Style Sheet (CSS) is a language that is used to interact with and style HTML, changing the way it looks accroding to a series of rules set by us. CSS is what make websites look nice.

CSS can be applied in a number of ways:

- The

styleattribute within the HTML tag like<h5 style="color:blue;text-align:center;":></h5>. The semicolon is used to separate different CSS properties that are passed to style. - The

<style></style>tags. This is useful to use when reusing the same styling many times throughout a page. The listed properties will apply to all of the tags that are listed. For example, we can add this in the middle of our HTML page: ```html

The above styling basically tells everything with `<h3></h3>` content to be blue and center-aligned. This way we don't need to repeat this thing a million time: `<h3 style="color:blue;text-align:center;">`. The styling applies to the whole HTML file.

- A separate `.css` file. To use this stylesheet, we need to add a reference to it on our HTML page like this: `<link rel="stylesheet" href="path/to/style.css">`. This is a better paradigm to use because it separates two distinct different functions: structure (HTML) and style (CSS). This makes the codes easier to read and maintain.

Some common CSS properties are:

/The ones that take arguments in pixels often can also take a percentage or simply `auto`./

- `color: blue`, `color: #0c8e05` : can be 1 of `140 named colors, or a hexadecimal value that represents an RGB value

- `text-align: left` : aligns text to left; other possible arguments are center, right, or justify

- `background-color: teal` : sets the background to a color, which is the same format as the color property

- `height: 150px` : sets the height of an area

- `width: 150px` : sets the width of an area

- `margin: 30px` : sets the margin around all four sides of an area

- can also be broken up into margin-left, margin-right, margin-top, and margin-bottom

- `padding: 20px` : sets the padding around text inside an area

- can be broken up the same way as margin

- `font-family: Arial, sans-serif` : sets the font family to be used

- a comma-separated list provides alternatives in case a browser doesn’t support a specific font

- generic families such as `sans-serif` will use browser defaults

What happens is when a web browser sees this, it will try to accomodate the first argument (`Arial`). If the browser does not have this it will resort to using the `sans-serif` font which is a generic family.

This is why if you want to use some fancy uncommon fonts, it's better to have the font with the html page.

- `font-size: 28px` : sets the font size

- `font-weight: bold`: sets the font weight to quality, a relative measure (lighter), or a number (200)

- `border: 3px solid blue`: sets a border around an area

There are a lot CSS properties that can be used in different ways. [[https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS][Check out this doco]].

### Sectioning with HTML and CSS

We can also divide our code into different sections for styling purposes. There are two special tags that allow us to break up our page into sections:

- `<div></div>`: *Vertical* division of a webpage.

- `<span></span>`: Section of a webpage inside an element, for example text.

Both of these don't really do much by themselves. However they allow us to label different sections of our webpage.

Different sections of a webpage can be referenced with `id` and `class` attributes, which are inside `div` or `span`. `id` identifies unique elements whereas there can be any number of an element with a given `class`.

`id` tags can be referenced in CSS with `#id` and `class` tags can be referenced with `.class`.

For example.. if we do `<div id="hello">` in our HTML page, we can then use `#id {..}` in the CSS stylesheet to target all those `div` elements with `id="hello"`..

# Lecture 1 - Git, HTML, CSS Extended

## More on Git

[[./images/gitmerge.png]]

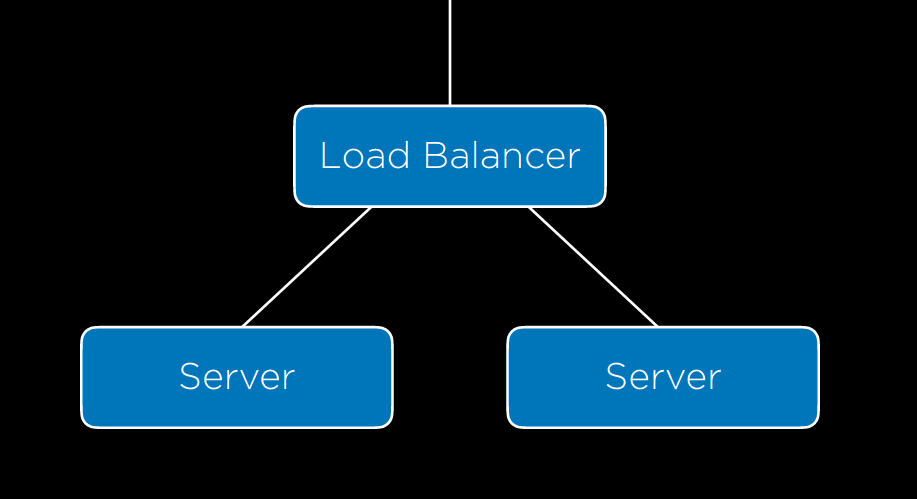

'Branching' is a feature of Git that allows a project to move in multiple different directions simultaneously. There is one *master* branch that is always usable but any number of branches can be created to develop new features. Once these changes are ready, they can be merged in to *master*.

When we are working in a Git repository, the `HEAD` refers to the current branch being worked on. When a different branch is 'checked out', the `HEAD` changes to indicate the new working branch.

When we merge a branch back into `master`, there is a possibility for merge conflict. These can be resolved in the same way that was discussed in Lecture 0.

When we have worked on a local branch and that branch does not exist on the remote branch. If we do a simple `git push`, Git will throw a fatal error because the current branch that we are working on has no upstream branch. In order to push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, we have to use: `git push --set-upstream origin <branch name>`.

Some of the commands that are related to branching:

- `git branch`: list all the branches currently in the repository.

- `git branch <name>`: create a new branch called `name`.

- `git checkout <name>`: switch current working branch to `name`

- `git merge <name>`: merge branch `name` *into current working branch* (normally `master`).

Any version of a Git repository that is not stored locally on a device is called a *remote*. *Origin* is used to refer to the remote from which the local repository was originally downloaded from.

Some of the git commands that are related to remotes:

- `git fetch`: download all of the latest commits from a remote to local device.

- `git merge origin/master`: merge `origin/master`, which is the remote version of a repository normally downloaded with `git fetch`, into the local existing `master` branch.

- `git pull` is equivalent to `git fetch && git merge origin/master`.

A *fork* of a repository is an entirely separate repository which is a copy of the original repository. A forked repository can be managed and modified like any other, all without affecting the local copy.

Open source projects are often developed using forks. There will be one central version of the software which contributors will fork and improve on. When they want these changes to be merged into the central repo, they submit a *pull request*. A Pull request can be made to merge a branch of a repository with another branch of the same repository or even a different repository.

Pull requests are a good way to get feedback on changes from collaborators on the same project.

## More on HTML

The `<a href="link/to/page"></a>` can be used for a hyperlink text. It can also be used to link to a local content marked by `#id`.

`<input type="radio"> Option 1` radio-button option for a form, where only 1 out of all the options may be selected.

There are a lot of new useful tags with HTML5, however not all browsers especially older ones will support these features. However, these new features can be used with increasing confidence that they will be rendered appropriately for a significant portion of the users.

For example, in HTML4 we may have seen something like this: `<div class="header">` whereas with HTML5 your syntax can look like this: `<header>`.

## More on CSS

[[./images/CSSSelectors.png]]

CSS Selectors can be used to select different parts of a website to style in particular ways. Some example below:

- Select `h1` and `h2`:

```css

h1, h2 {

color: green;

}

- Select all

lithat are descendent ofol. Note that these are not necessary immediate descendants. In order to to do this we just use the space separator.ol li { color:red; } - Select all

lithat are immediate children ofolby using the > separator.ol > li { color:darkgreen; } - Select all

inputfields with attributetype=text:input[type=text] { background-color:whitesmoke; } - Select all

buttonswith the pseudoclasshover:button:hover { background-color: orange; }(/A pseudo-class is a special state of an HTML element. In the example below, the

hoverstate is whether or not the cursor is hovering over a button. Pseudoclasses are generally used to style our pages according to use activities and interaction with the page./) - Select all

beforepseudoelements of the elementa:a::before { content: "\21d2 Click here: "; font-weight: bold; }(/A pseudoelement is a way to affect certain parts of an HTML element. In the above example, the

beforeselector appliescontentwith its included styling before the content of allaelement.With that style, any<a>block will have “.. Click here: “ appended before the content of the block./)

(/21d2 is a hexidecimal value of a Unicode icon which can represent symbol like an emoji./)

- Select all

selectionpseudoelement of the elementp:p::selection { color:red; background-color: brown; }

Responsive design

Responsive design is the idea that a website should look good regardless of the platform it is viewed on (computer vs mobile phone).

One way we can do this is by using a ‘media query’:

<style>

@media print {

.screen-only {

display:none;

}

}

</style>

<body>

<p class="screen-only"> This content will not appear when printed </p>

</body>

The @media is a media query that means the following CSS will be only applied in certain situations. For example in the above example, the display:none is applied to .screen-only which means that when the page is printed, that line will not appear.

Another example is:

@media (min-width: 500px) {

body {

background-color: green;

}

}

@media (max-width: 499px) {

body {

background-color: yellow;

}

}

The above means: when the width of the screen is at least 500 pixel, the background of body will be green. If it’s less than 499px, the background of body will be yellow instead.

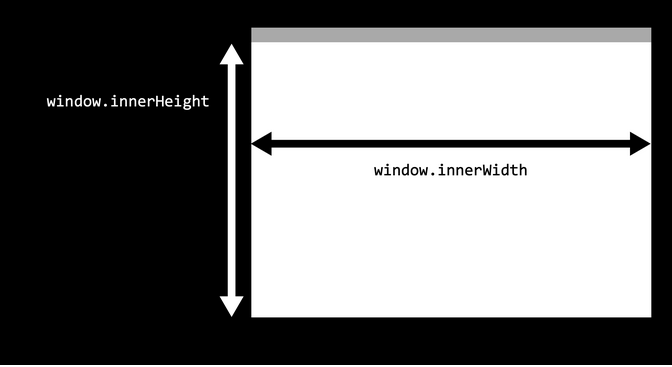

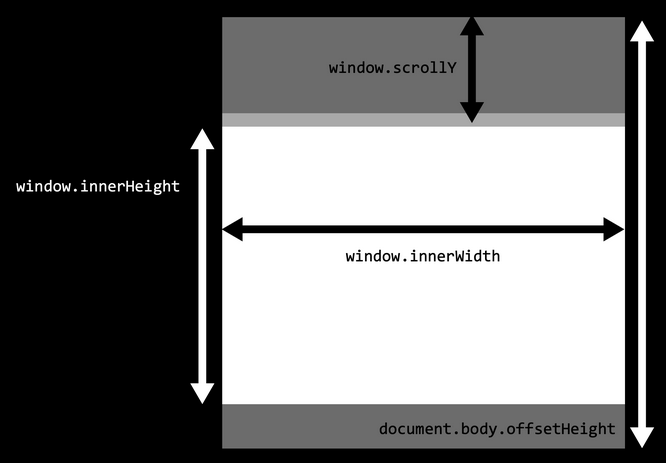

In order to interact with the screen size, the following must be included in the <head></head>: <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width", initial-scale=1.0">. viewport is the visible area on the which the screen is being displayed. content refers to the entire webpage the width of which is being set to device-width.

Another tool that is regularly used is flexbox. Flexbox allows for the reorganization of content based on the size of the viewport.

.container {

display: flex;

flex-wrap: wrap;

}

By applying the two settings above, content will wrap vertically if necessary so no content is lost when the width of the screen is shrunk.

A grid of content can be achieved in a similar fashion:

.grid {

display: grid;

grid-column-gap: 20px;

grid-row-gap: 10px;

grid-template-columns: 200px 200px auto;

}

By setting display: grid, all the different characteristics of a grid layout can be used to format content. When defining grid-template-columns, for example, the last column can be set to auto which fills up however much the screen space there may be left. If multiple columns are set to auto they will equally share the remaining space.

Bootstrap

Bootstrap is a CSS Library written to help make clean and responsive and nice-looking websites without having to remember all the gritty details about flexboxes or grids everytime a layout needs to be created.

To use Bootstrap, we only need to add a single line which links Bootstrap’s CSS stylesheet:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.1.1/css/bootstrap.min.css" integrity="sha384-WskhaSGFgHYWDcbwN70/dfYBj47jz9qbsMId/iRN3ewGhXQFZCSftd1LZCfmhktB" crossorigin="anonymous">

By adding the above line, Bootstrap’s CSS will make everything look a little cleaner and more modern. However its real power comes out with its layout system. Bootstrap uses a column-based model where every row in a website is divided into 12 individual columns and different elements can be alloted a different number of columns to fill.

Bootstrap’s columns and rows are referenced in HTML with class="row" and class="col-3" attributes where the number after col- is the number of columns the elements should use.

Elements can take up a different number of columns based on the size of the screen with attributes like class="col-lg-3 col-sm-6" which means on a small screen, 6 columns will be used but in large screen, 3 columns will be used. If another rows needs to be added, Bootstrap will do it automatically. This is a much easier alternative to Flexbox because Bootstrap does this behind the scene.

Bootstrap has a whole host of other pretty components which can easily be applied by simply adding the appropriate class attribute to an element. We can visit the [[https://getbootstrap.com/docs/4.1/components/alerts/][Bootstrap’s documentation]] for an extensive list.

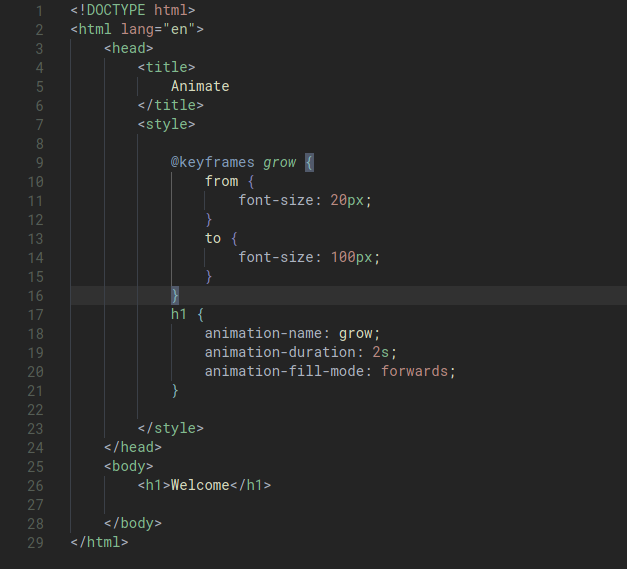

Sass

Sass is an entirely new language built on top of CSS which gives it a little more power and flexibility when designing CSS stylesheets and allow for the generalization of stylesheets in a programmatic way.

Ultimately, Sass makes writing CSS easier.

In ordet to use Sass, we have to [[https://sass-lang.com/install][install it]]. Once we have installed this we can execute sass style.scss style.css to compile our Sass file style.scss into sass.css which can be linked to and intepreted by out HTML file.

If we are sick of recompiling, we can do sass --watch style.scss:style.css to automatically recompile style.scss as style.css whenever style.scss is modified. Additionally, many website deployment systems like GitHub pages have built-in support ofr Sass. Say, if we push a .scss file to Github, GitHub pages will render it for us.

Sass allows many features, one of which is the use of variables which are defined like this: $color:red;. Anywhere $color is passed as a vlue for a CSS property e.g color: $color, red will be used.

Another features of sass is nesting which is a more concise way to style elements which are related to other elements in a certain way:

div {

font-size: 18px;

p {

color: blue;

}

ul {

color:green;

}

}

In the above example, all the p elements inside div will have the color:blue but also font-size : 18px while all ul inside div will have color: green but also font-size : 18px.

A very useful feature is inheritance which is simialr to object-oriented concept. Sass’s inheritance allows for slight tweaking of a general style for different components.

%message {

font-family: sans-serif;

font-size: 18px;

font-weight: bold;

}

.specificMessage{

@extend %message;

background-color: purple;

}

%message defines a general pattern than can be inherited in other style definitions using extend %message syntax. In addition to the inheritance, other different styling can also be applied.

Lecture 2

Python..

Lecture 3 - Django

Django is a Python web framework that is used to generate dynamic web pages using Python. Together with HTML and CSS, Django allows us to build a dynamic web application. Django contains a set of tools that are already built for us that makes it easy to make a fully fledged web application. It deals with the boring stuff for us so we can deal with the interesting web page content.

Create a django project:

django-admin startproject PROJECT_NAME

After a folder with PROJECT_NAME will be created in the current working directory. When we look into this folder there are a few important but boring files:

- manage.py: this file is used to execute Django command to interact with our project.

- settings.py: contains important configuration settings. It comes with default config but we can change them

- urls.py: This is like a table of content for our Django web application. It contains the URLs that can be visited.

We can run the web app by interacting with manage.py like this: python manage.py runserver.

Apps

The way that Django is structured is that each Django project generally contains one or more Django applications. One project may have multiple apps within it. For example, on Google webpage we have multiple distinct apps like Google Search, Google Image, Google Map.

In Django we create an app by python manage.py startapp APP_NAME.

After this, a directory called APP_NAME will be created in our project directory. Within this app directory there are a few files.

After we have created the app, we’ll need to install the app into our project. We do it by going into the project’s settings.py file. In the list variable INSTALLED_APPS we need to add the name of our new app into the list.

views

We can set up the page the our users see when visiting an app. To do this we take a look at the views.py file in the app folder.

Each view is something the user might want to see.

To create a basic view can do this:

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponse

def home(request):

return HttpResponse('Hello world!')

urls

Now we need to tell the app when to respond or what particular URL should be visited to display the view/ HTTP Response. We need to do this by creating a urls.py in our particular app.

For separation purpose, we mostly want to create a urls.py file in each individual app, in addition to the urls.py in the project folder.

What urls.py need is a list variable urlspattern which is a list of URLs that are accessible for this particular app.

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path("", views.index, name="index")

]

In the above example, the name argument is optional. The idea is that this name can be used later to reference this url in other parts of our application.

After we do this within the individual app urls.py file, we’d also need to add the route to this app in the main project’s urls.py file. We can add this to the urlpatterns variable:

urlpatterns = [

path('hello/', include("hello.urls"))

]

The above basically means, if we go to /hello/, use or “include” the route from hello/urls.py.

views with params

We can also create view function that takes additional parameter like name:

def greet(request, name):

return HttpResponse(f"Hello, {name.capitalize()}!")

Then add this in urls.py:

urlpatterns = [

path("<str:name>", views.greet, name="greet")

]

What’s going is that we have a dynamic path that takes a name parameter and returns a dynamic view page that uses the name variable to return the view.

templates

In Django, we can separate the HTML response from the Python code. Instead of putting the entire HTTP response in the return statement of the view function in the views.py file, we can have distinct HTML file. This file is called a template.

def index(request):

return render(request, "hello/index.html")

Now we need to create the template. We do it by creating a folder templates within our app, then create another folder called “hello” to store our HTML template in. We could have done without the hello/ bit and just sit our template in the templates/ folder, however we want to have namespaces in our templates. For example if we have 10 different apps each with their own index.html, we wouldn’t want to conflict them.

So, in our hello app we would have the index.html like this:

hello > templates > hello > index.html

context

Let’s change our greet function, which is currently just:

def greet(request, name):

return HttpResponse(f"Hello, {name.capitalize()}!")

Let’s say we want to render an entire page. We can do:

def greet(request, name):

return render(request, "hello/greet.html", {

"name" : name.capitalize(),

})

- The third argument in the render function is called a context. A context is all of the information that we’d like to provide to the template.

- When we render the template greet.html, that template is provided with information in the format of a dictionary with some a key name and its (dynamic) value. Within the template, we can then use the variable name.

Then, our template can access the name variable, using the double curly braces, like this:

hello > templates > hello > greet.html:

There is a lot of different things happening across different files. The main purpose for this is to have each of them with separate purposes, or act as a separate component of our web application.

Django template language - other functions.

In the above example, we learnt how to access a variable within our template. The Django template language offers other functionalities.

Using conditions in templates

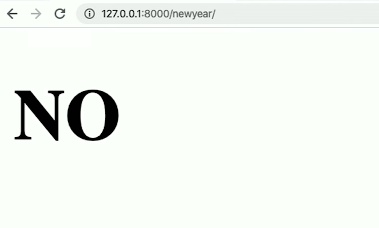

One very simple example that we can look at is https://isitchristmas.com.

Using Django, we can implement Python conditions to create a very similar web page.

Let’s say if we want to create something like “is it new years?”.

python manage.py startapp newyear

then, add 'newyear' into INSTALLED_APPS within the project’s settings.py.

then, go to project’s urls.py and add a new path:

urlpattterns = [

path('newyear/', include("newyear.urls"))

]

then

touch newyear/urls.py

then within the newyear/urls.py:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpattern = [

path("", views.index, name="index")

]

/(only one single view index when the routed URL is /newyear.)/

then in newyear/views.py:

from django.shortcuts import render

import datetime

def index(request):

now = datetime.datetime.now()

return render(request, "newyear/index.html", {

"newyear": now.month == 1 and now.day == 1

})

)

/(The newyear variable will be a boolean variable, equating to True if it’s Jan 01 and False otherwise.)/

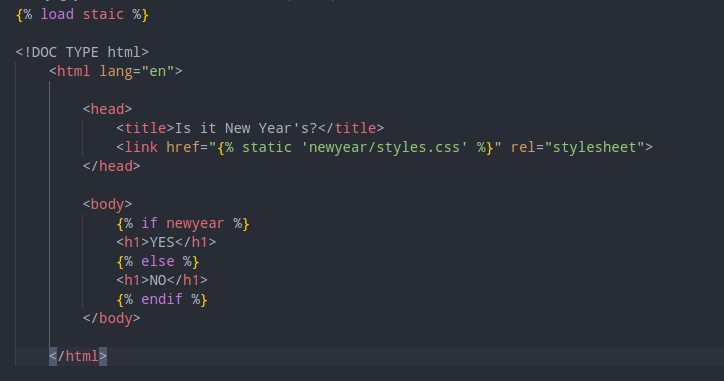

then in newyear/templates/newyear, we create index.html.

Note that in the Django template language, we need to end our if statement with an endif.

If a client decide to inspect the source of our HTML, they would only see the final product of the template because the conditioning happens server-side, i.e all they see is “No”.

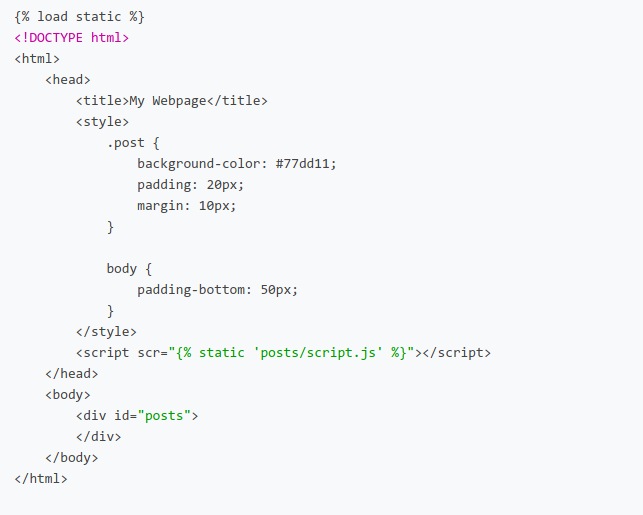

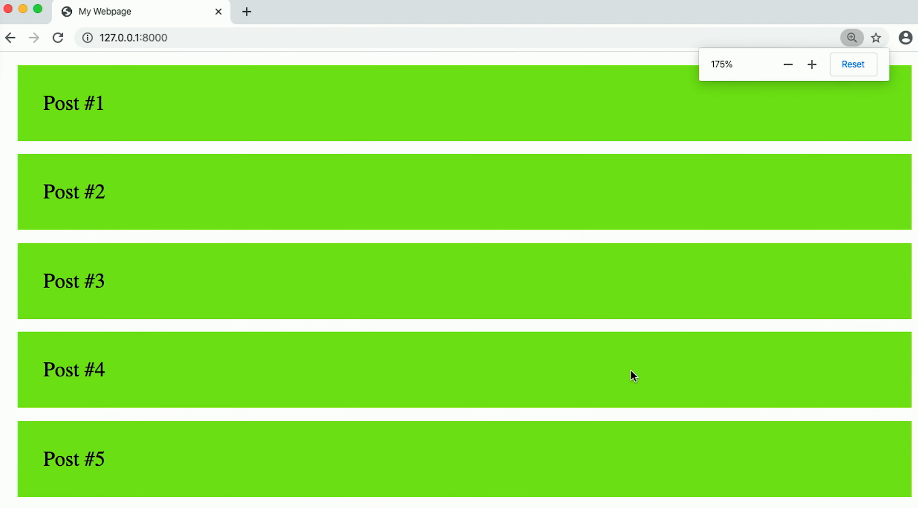

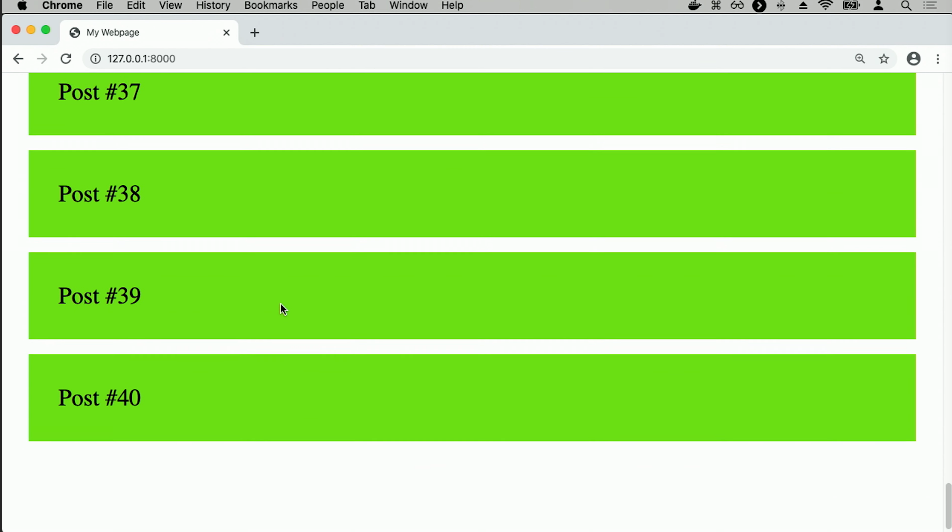

Styling

Django has a special system to deal with unchanged CSS stylesheets, so-called static files.

The way that we can add static files is to add a folder static/ inside our app that will be used to contain all the static files that we will be using for our Django app (not project). Inside this static/ folder we’d also need a folder APP_NAME, like this:

newyear > static > newyear > styles.css

h1 {

font-family: sans-serif;

font-size: 90px;

text-align:center;

}

Then, in our newyear/index.html, we’d need to load our static then reference the actual stylesheet, like this:

We could have hard-code the URL of our stylesheet instead of using Django dynamic language and the ‘static’ keyword. However, doing it this way is better, especially if we have large web application.

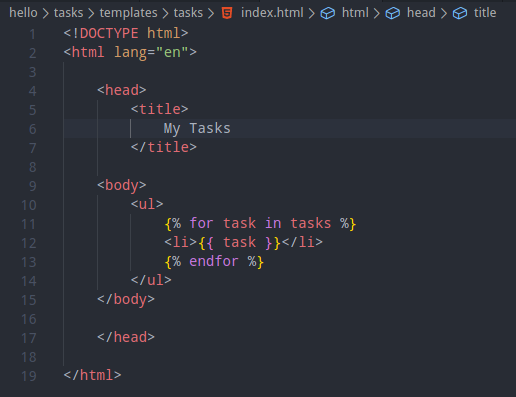

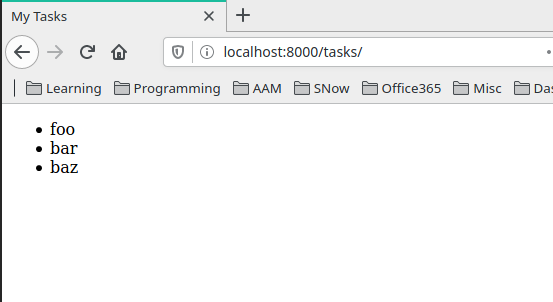

Building a to do list

Start the app

$ django-admin startapp tasks

Install the app and include the url routing of tasks

hello/hello/settings.py:

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'tasks'

...

]

hello/hello/urls.py:

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include

urlpatterns = [

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

path('tasks/', include("tasks.urls"))

]

Configure the routing, view and index template of tasks

apps/tasks/urls.py:

from django.urls import path

from. import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name="index")

]

then the view: apps/tasks/views.py:

from django.shortcuts import render

tasks = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] # Some placeholder used for MVP

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": tasks

})

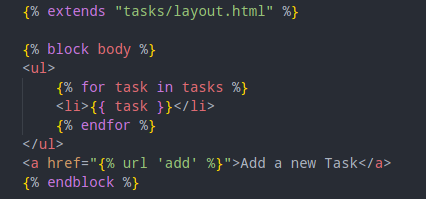

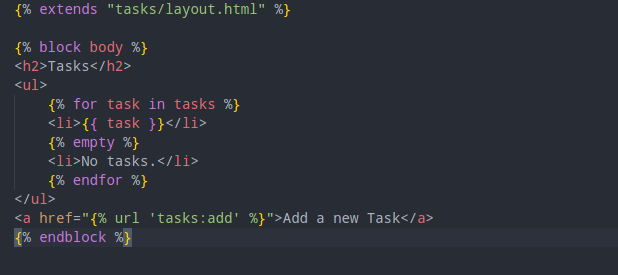

and finally the template which will be using the tasks context variable: /tasks/templates/tasks/index.html:

Task Add function

In the views module we create a new function add():

def add(request):

return render(request, "tasks/add.html")

then configure the urs:

from django.urls import path

from. import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name='index'),

path('add/', views.add, name='add')

]

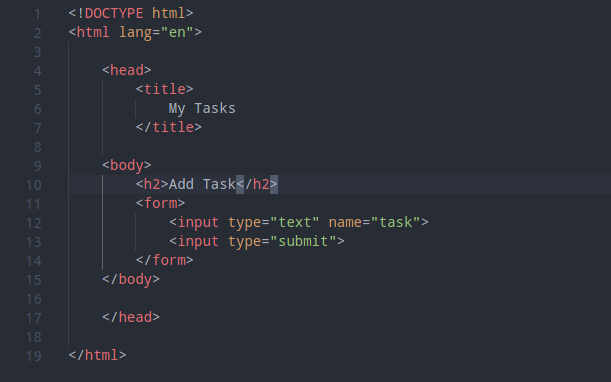

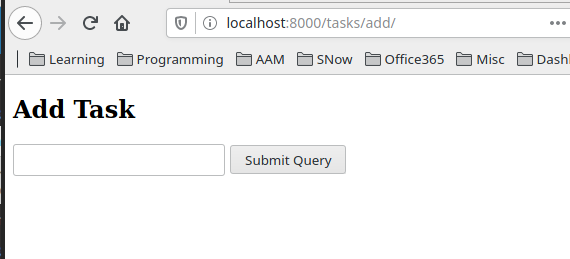

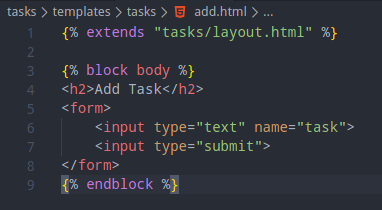

the template templates/tasks/add.html:

template inheritance

In the above example what we did was copying the layout of the HTML file from index.html to add.html. Whenever we find ourselves doing copy-pasting like this it’s a good example to stop and pause to think if there is any more efficient way of doing things.

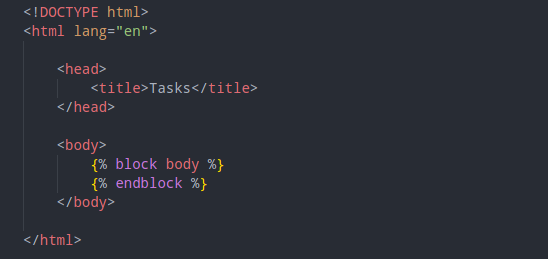

With pure HTML, there isn’t. However with Django we can implement template inheritance. What we are doing is to set up a layout template that will be used by both index.html and add.html.

tasks/templates/tasks/layout.html:

The block bit is the dynamic element.

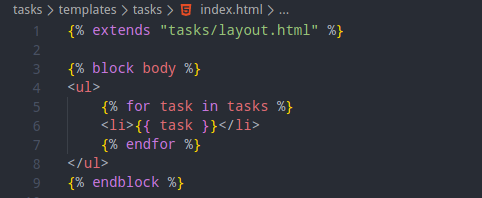

We can then go back to index.html and only leave the unique elements in index template and include an extends statement and state the block body.

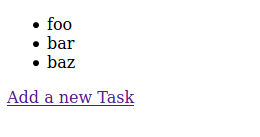

same thing with the add.html file:

We may want to implement a link to navigate from one page to the other. Let’s do this by ultilizing Django feature which is to use the name of the page, not hardcode it: index.html:

This is made possible by specifying a name for each url path in the urls.py file.

We can avoid namespace collision by doing these two things:

- First, add app_name variable in the urls.py file: ```python from django.urls import path from. import views

app_name = tasks urlpatterns = [ path(‘’, views.index, name=’index’), path(‘add/’, views.add, name=’add’) ]

- Then, reference the url like this in the *add.html* file, with the app_name, followed by colon, then the template name:

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_171435_QUP4jb.png">

as well as the *index.html* file:

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_171458_TXXuGe.png">

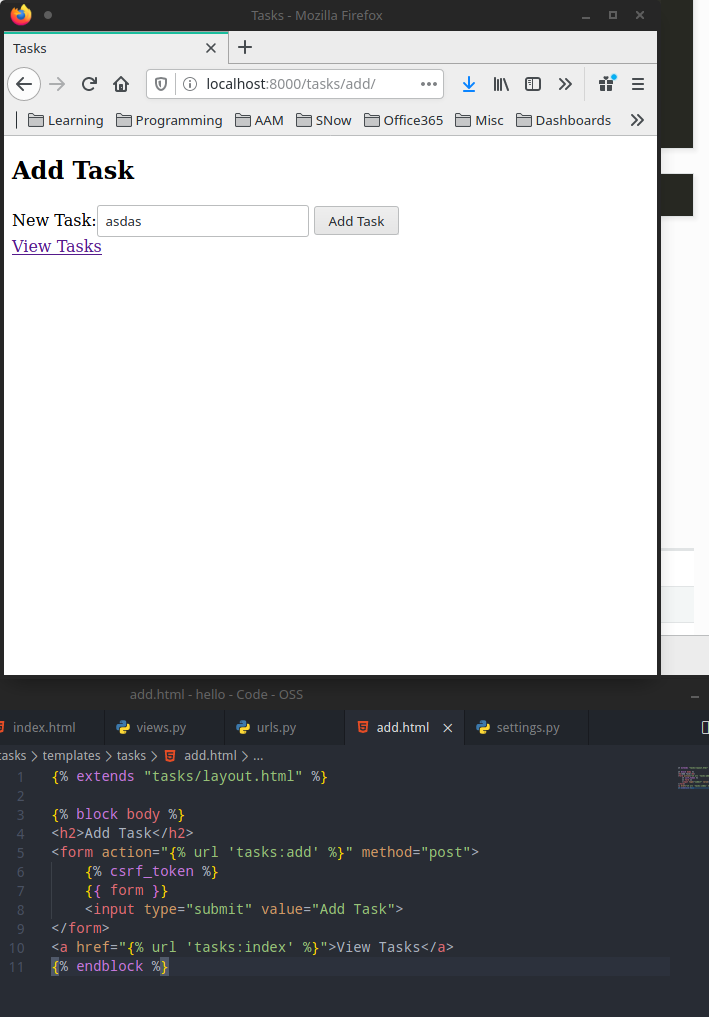

#### configure form submission and POST method

We first need to configure the form element on our template to 1) send the submission to the right view `tasks:add` and use *POST* method. This method should be used for any action that changes the state of any component in our application.

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_172627_fvkNqi.png">

after this, let's try to add a random task and hit submit..

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_172702_akij69.png">

The 403 errors mean forbidden/ no permission.

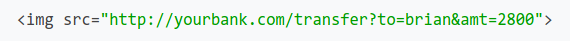

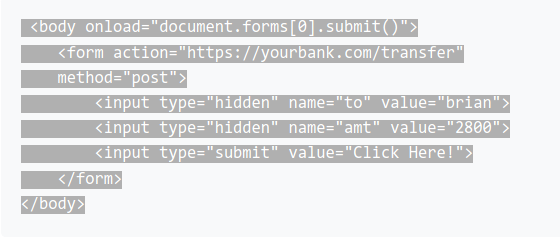

What the hell is CSRF? It's "Cross-site request forgery" which means a security vulnerability that exists on a form. Theoreotically someone could trick our users into posting a form data to our application. CSRF authentication is turned on by Django on default. It's by a thing called *MiddleWare*:

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_173151_cLv6cK.png">

What we need to do is to add a hidden csrf token into our form. This is unique and is generated every session a user opens our page. When our user submits the form, the token gets submitted with the form and is used to check to make sure that the token is indeed valid and the form submission is OK to go on.

This is very easy:

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_173235_69YW8A.png">

If we view the source of our add page, we can see the csrf token:

<img class="mx-auto w-1/2" src="/assets/img/orgNotesImages/CS50's Web Programming with Python and Javascript.org_20200709_173316_ViJ808.png">

and now the form will submit without error.

However the submission doesn't actually do anything.

What we have done is create form ourselves and write it from scratch in our HTML template. However we can also explore an alternative which is to use the Django built-in form features.

Let's do this.. *views.py*. First we need to create a class that inherits from the Django form module. Then, we pass the class to our template.

```python

from django.shortcuts import render

from django import forms

tasks = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] # Some placeholder used for MVP

class NewTaskForm(forms.Form):

task = forms.CharField(label="New Task")

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": tasks

})

def add(request):

return render(request, "tasks/add.html", {

"form": NewTaskForm()

})

Then we can access the form in our add.html template:

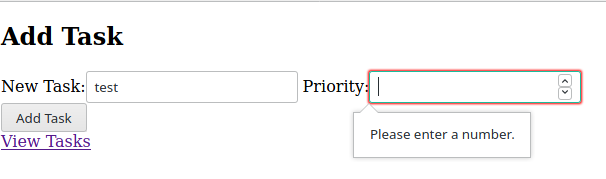

The powerful thing about this is if we need to change anything in our form, we can do it within views.py in Django instead of doing it on the template. Let’s say we want to put a priority field in:

views.py

from django.shortcuts import render

from django import forms

tasks = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] # Some placeholder used for MVP

class NewTaskForm(forms.Form):

task = forms.CharField(label="New Task")

priority = forms.IntegerField(label="Priority", min_value=1, max_value=10)

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": tasks

})

def add(request):

return render(request, "tasks/add.html", {

"form": NewTaskForm()

})

Django also does the data validation for us. This is client-side validation which is not done by the server (we can see this by viewing the source of the page).

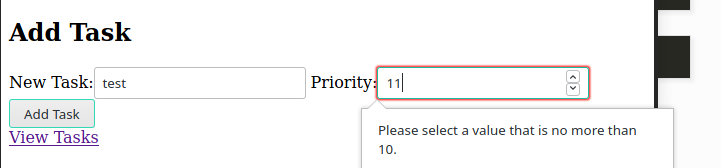

We can also do server-side validation. We can do it by editing the add() function to be able to handle a POST request. We will also change the max_value of priority to 5 on the server. Note that the client session would still have max_value=10 cached so they don’t know of this new max_value yet.

views.py

from django.shortcuts import render

from django import forms

tasks = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] # Some placeholder used for MVP

class NewTaskForm(forms.Form):

task = forms.CharField(label="New Task")

priority = forms.IntegerField(label="Priority", min_value=1, max_value=5)

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": tasks

})

def add(request):

if request.method == "POST":

form = NewTaskForm(request.POST) # This variable contains all data submitted by user

if form.is_valid():

task = form.cleaned_data['task']

tasks.append(task)

else:

# Send the form back to the user with existing details

return render(request, "tasks/add.html",

{

"form": form

})

return render(request, "tasks/add.html", {

"form": NewTaskForm()

})

Then if we submitted 8 in priority, which would previously be accepted by the server, we’d see this:

This is why we generally want both client-side and server-side validation.

What if we want to redirect users to the index page after they have added a task? We can do this:

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponseRedirect

from django.urls import reverse

...

def add(request):

if request.method == "POST":

form = NewTaskForm(request.POST) # This variable contains all data submitted by user

if form.is_valid():

task = form.cleaned_data['task']

tasks.append(task)

return HttpResponseRedirect(reverse("tasks:index"))

else:

# Send the form back to the user with existing details

return render(request, "tasks/add.html",

{

"form": form

})

....

With this, after use submits a Task and hit the submit button they’d be redirected back to the index page.

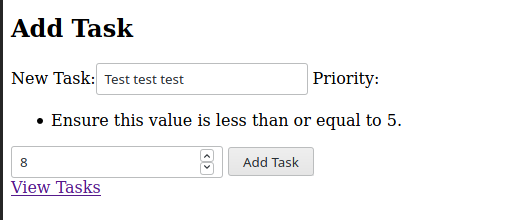

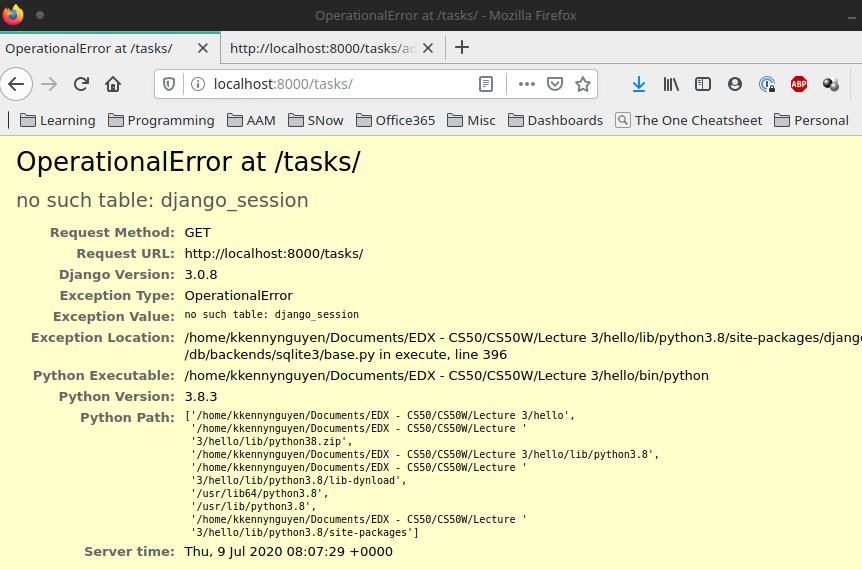

Session

Now, we implement session which basically enables Django to remember session information. Each of our session should have a separate task list

views.py

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponseRedirect

from django.urls import reverse

from django import forms

class NewTaskForm(forms.Form):

task = forms.CharField(label="New Task")

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

if "tasks" not in request.session:

request.session["tasks"] = []

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": request.session["tasks"]

})

def add(request):

if request.method == "POST":

form = NewTaskForm(request.POST) # This variable contains all data submitted by user

if form.is_valid():

task = form.cleaned_data['task']

tasks.append(task)

return HttpResponseRedirect(reverse("tasks:index"))

else:

# Send the form back to the user with existing details

return render(request, "tasks/add.html",

{

"form": form

})

return render(request, "tasks/add.html", {

"form": NewTaskForm()

})

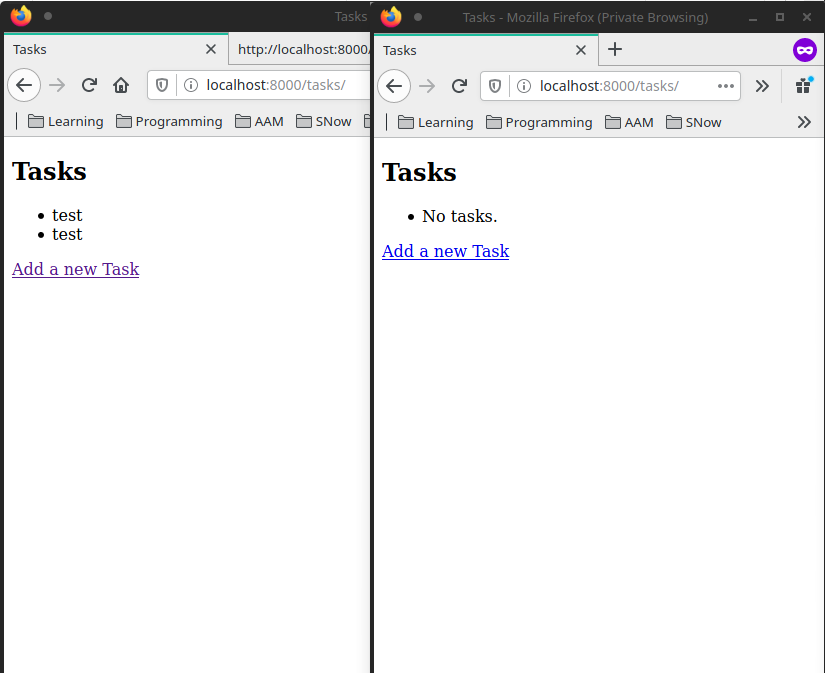

However, if we go to our tasks now, we’d see:

To address we’d need to create all of the default tables inside our Django database by running:

python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, auth, contenttypes, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying contenttypes.0001_initial... OK

Applying auth.0001_initial... OK

Applying admin.0001_initial... OK

Applying admin.0002_logentry_remove_auto_add... OK

Applying admin.0003_logentry_add_action_flag_choices... OK

Applying contenttypes.0002_remove_content_type_name... OK

Applying auth.0002_alter_permission_name_max_length... OK

Applying auth.0003_alter_user_email_max_length... OK

Applying auth.0004_alter_user_username_opts... OK

Applying auth.0005_alter_user_last_login_null... OK

Applying auth.0006_require_contenttypes_0002... OK

Applying auth.0007_alter_validators_add_error_messages... OK

Applying auth.0008_alter_user_username_max_length... OK

Applying auth.0009_alter_user_last_name_max_length... OK

Applying auth.0010_alter_group_name_max_length... OK

Applying auth.0011_update_proxy_permissions... OK

Applying sessions.0001_initial... OK

We can also update the template to check if the task list is empty:

We also need to update our views.py file to refer to request.session["tasks"] instead of the previously configured global variable.

views.py

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponseRedirect

from django.urls import reverse

from django import forms

class NewTaskForm(forms.Form):

task = forms.CharField(label="New Task")

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

if "tasks" not in request.session:

request.session["tasks"] = []

return render(request, 'tasks/index.html', {

"tasks": request.session["tasks"]

})

def add(request):

if request.method == "POST":

form = NewTaskForm(request.POST) # This variable contains all data submitted by user

if form.is_valid():

task = form.cleaned_data['task']

request.session["tasks"] += [task]

return HttpResponseRedirect(reverse("tasks:index"))

else:

# Send the form back to the user with existing details

return render(request, "tasks/add.html",

{

"form": form

})

return render(request, "tasks/add.html", {

"form": NewTaskForm()

})

Now, the task list is individual to each session that is stored by the browser cookie. We can test this by using an in cognito browsing session:

Lecture 4 - Django SQL

Overview

What Django allows us to do is to build a dynamically generated web application, instead of just static content.

Where Django gets even more powerful is when we dive into the world of databases. Django allows us to have an abstract layer on top of the SQL database layer. With Django, we interact with the SQL database by not writing direct SQL queries but by interacting with Python Classes and Objects that we can refer to as Models. Migrations are a technique that allows us to update the ongoing changes that are made in the underlying database.

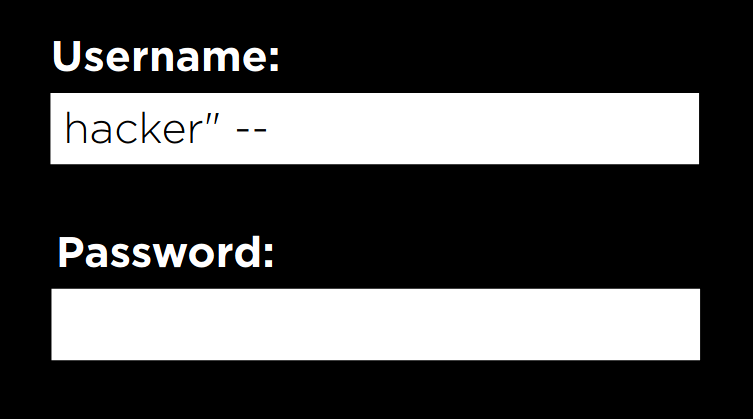

There are plenty of reasons why we want to use Django abstract layer of database instead of interacting with it by using SQL queries. One of them is that with Python, we don’t have to worry about the nuances of the SQL languages and the possible vulnerabilities that we might inadvertantly expose our program to. For example, SQL Injection, Race Condition Problem..etc.

Django Model Basic

Django Models are a way of representing SQL data inside our Django applications.

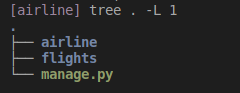

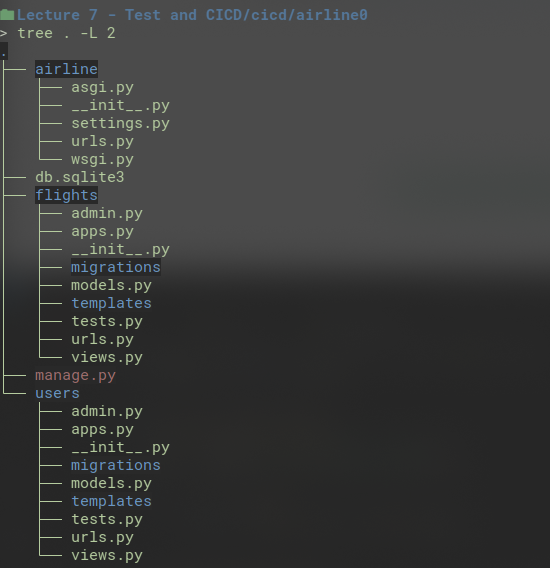

Let’s start working on an airline project with a flights app.

After configuring the apps and urls, let’s look into flights/models.py. We’ll start by creating a Flight model.

from django.db import models

# Create your models here.

class Flight(models.Model):

origin = models.CharField(max_length=64)

destination = models.CharField(max_length=64)

duration = models.IntegerField()

This model should contain certain attributes that a Flight has. For the example above, we’ll just have the three most basic attributes that a flight would have.

models.py

from django.db import models

# Create your models here.

class Flight(models.Model):

origin = models.CharField(max_length=64)

destination = models.CharField(max_length=64)

duration = models.IntegerField()

After this file is saved, nothing would have been saved on our Django application. In order to “deploy the changes” we need to tell Django update the database to update the information about the model that we just created.

This process, in Django is creating a migration. It’s a two-step processes:

- Here are some changes to the database (creating the migration).

- Take the migration steps/ instructions and apply them to the underlying database.

What we do is run these command:

python manage.py makemigrations

Migrations for 'flights':

flights/migrations/0001_initial.py

- Create model Flight

After this, there should be a migrations/ directory and it contains a file that contains the instructions how to manipulate the database to reflect the changes we have made.

And then we can do:

python manage.py migrate

After this, we should be able to see a database file db.sqlite3 in our Django directory.

We can query from the database with Django Shell.

python manage.py shell

We can create a database entry without any SQL query, just using Python, like this.

>>> from flights.models import Flight

>>> f = Flight(origin="New York", destination="London", duration=10)

>>> f.save()

We can query our data, like this:

>>> from flights.models import Flight

>>> print(Flight.objects.all())

<QuerySet [<Flight: Flight object (1)>]>

To make our model return a readable string, we can add the __str()__ function for our model:

flights/models.py

from django.db import models

# Create your models here.

class Flight(models.Model):

origin = models.CharField(max_length=64)

destination = models.CharField(max_length=64)

duration = models.IntegerField()

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.id}: {self.origin} to {self.destination}"

Now, if we retry, the result looks nicer:

>>> from flights.models import Flight

>>> print(Flight.objects.all())

<QuerySet [<Flight: 1: New York to London>]>

>>> Flight.objects.first()

<Flight: 1: New York to London>

We can also delete the flight object.

>>> f = Flight.objects.first()

>>> f.delete()

(1, {'flights.Flight': 1})

Django Models - abit advanced - #related_name#

Let’s make some changes to the models.

flights/models.py

from django.db import models

# Create your models here.

class Airport(models.Model):

code = models.CharFeild(max_length=3)

city = models.CharField(max_length=64)

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.city} ({self.code})"

class Flight(models.Model):

origin = models.ForeignKey(Airport, on_delete=models.CASCADE, related_name='departures')

destination = models.ForeignKey(Airport, on_delete=models.CASCADE, related_name='arrivals')

duration = models.IntegerField()

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.id}: {self.origin} to {self.destination}"

- The

on_delete=models.CASCADEsays that if an Airport is deleted, Django should also delete all the corresponding Flights. - The related_name is useful for when we have an airport, and want to see all Flights entry that correspond to that airport. In this example, if we have an airport, we can call “departure” to see all flights leaving that airport. Same with the destination and “arrival” field.

[airline] python manage.py makemigrations

Migrations for 'flights':

flights/migrations/0002_auto_20200728_1245.py

- Create model Airport

- Alter field destination on flight

- Alter field origin on flight

[airline] python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, auth, contenttypes, flights, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying flights.0002_auto_20200728_1245... OK

Now, we can enter Django shell and create some Airport objects.

>>> from flights.models import Airport

>>> jfk = Airport(code='JFK', city='New York')

>>> lhr = Airport(code='LHR', city='London')

>>> cdg = Airport(code='CDG', city='Paris')

>>> nrt = Airport(code='NRT', city='Tokia')

>>> jfk.save()

>>> lhr.save()

>>> cdg.save()

>>> nrt.save()

Then, we can create a Flight object.

>>> from flights.models import Flight

>>> f = Flight(origin=jfk, destination=cdg, duration=300)

>>> f.origin

<Airport: New York (JFK)>

>>> f.destination

<Airport: Paris (CDG)>

>>> f.destination.code

'CDG'

Then, we can use the related_name to see all flight leaving JFK:

>>> jfk.departures.all()

<QuerySet [<Flight: 1: New York (JFK) to Paris (CDG)>]>

Django Models - Show all objects in a view

First, the urls

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name='index')

]

Secondly, the views

from django.shortcuts import render

from .models import Flight

# Create your views here.

def index(request):

return render(request, 'flights/index.html',{

'flights': Flight.objects.all()

})

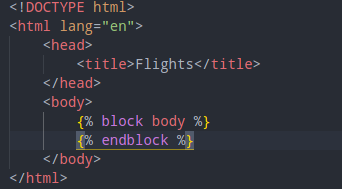

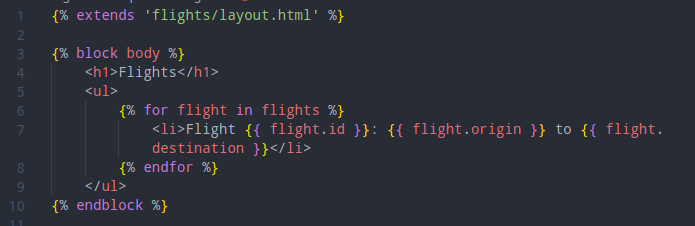

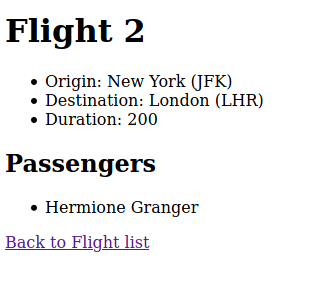

Then, the template

the layout.html:

then the actual index.html:

result

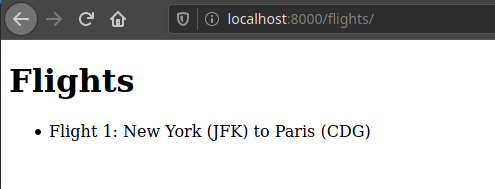

Let’s add a new flight

fPython 3.8.3 (default, May 17 2020, 18:15:42)

[GCC 10.1.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

(InteractiveConsole)

>>> from flights.models import *

>>> Airport.objects.all()

<QuerySet [<Airport: New York (JFK)>, <Airport: London (LHR)>, <Airport: Paris (CDG)>, <Airport: Tokia (NRT)>]>

>>> london = Airport.objects.filter(city='London')

>>> london

<QuerySet [<Airport: London (LHR)>]>

>>> london = Airport.objects.get(city='London')

>>> ny = Airport.objects.get(city='New York')

>>> f = Flight(origin=ny, destination=london, duration=200)

>>> f.save()

note:

- The

get()method would throw an error if there are more than one object.

Then, we refresh our page, and BAM:

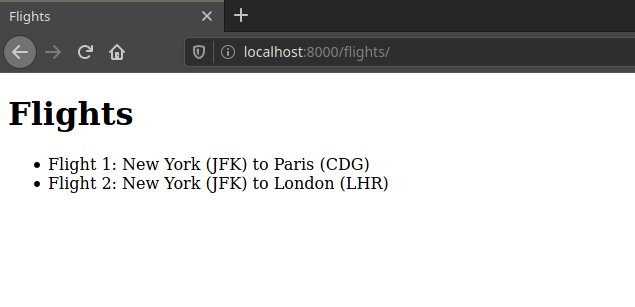

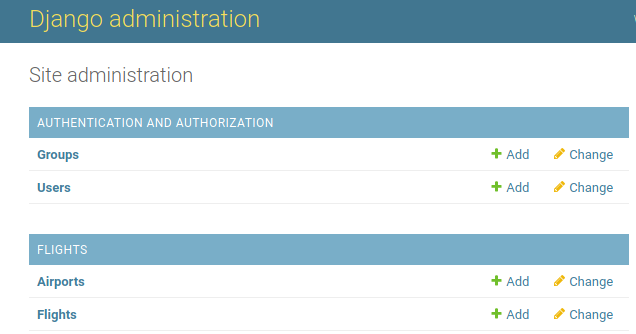

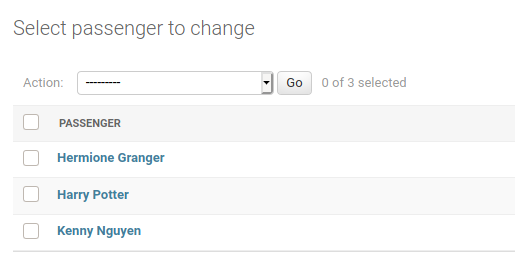

Django Admin

With the knowledge that we have now, if, say we want to build a module to allow our users to add a new flight to the database via the web interface, we could. However, Python Django is built with the principle that programmers should not be repeating codes. Therefore, Django already comes with the entire Django admin app which allows users to manipulate Django Models.

To log into the Admin App, we just need to:

python manage.py createsuperuser

If we go to the Admin page now, we’d only see this:

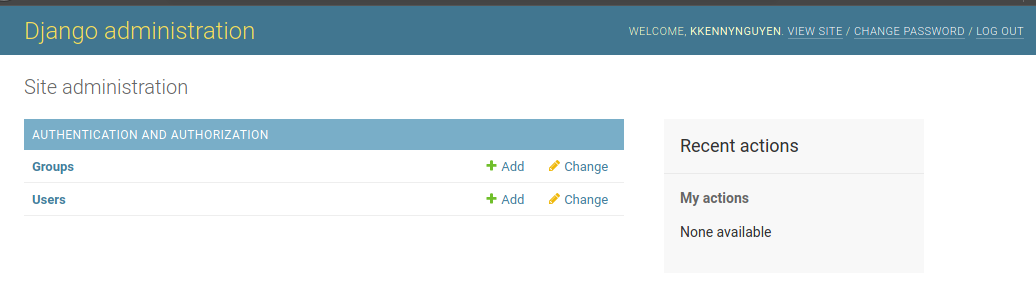

We need to configure our Admin app:

flights/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Flight, Airport

# Register your models here.

admin.site.register(Airport)

admin.site.register(Flight)

With this, we are telling the Django Admin App that “we would like to use the Admin App to manipulate flights and airports.”

Then, if we fresh our admin app:

Fancy up our page

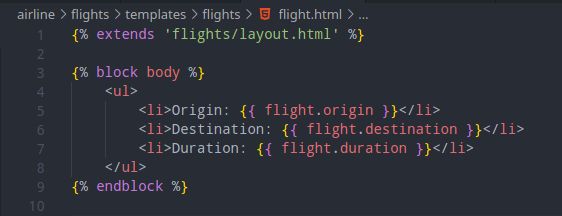

See individual flight

flights/urls.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name='index'),

path('<int:flight_id', views.flight, name='flight')

]

flights/views.py:

from django.shortcuts import render

from .models import Flight

def index(request):

return render(request, 'flights/index.html',{

'flights': Flight.objects.all()

})

def flight(request, flight_id):

flight = Flight.objects.get(id=flight_id) # We can also do "pk="

return render(request, 'flights/flight.html', {

'flight': flight

})

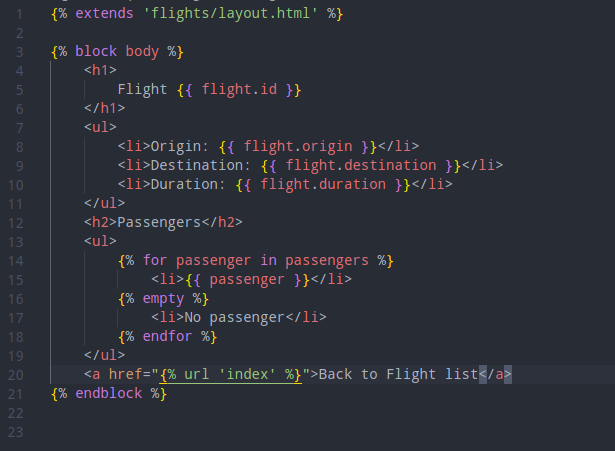

and then the template templates/flights/flight.html:

We can verify that the page is working:

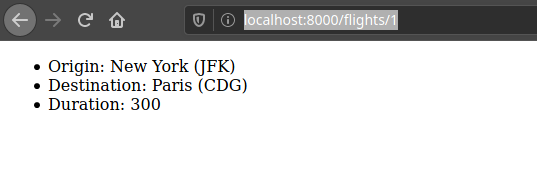

Add Passenger

Relationship between Passenter and Flights is many-to-many.

We add this class to the flights/models.py file

class Passenger(models.Model):

first = models.CharField(max_length=64)

last = models.CharField(max_length=64)

flights = models.ManyToManyField(Flight, blank=True, related_name="passenger")

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.first} {self.last}"

The related_name is for “I have a flight, show me all passengers that board this flight”.

[airline] python manage.py makemigrations

Migrations for 'flights':

flights/migrations/0003_passenger.py

- Create model Passenger

[airline] python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, auth, contenttypes, flights, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying flights.0003_passenger... OK

We then register our Passenger to the Admin site and add a few passenger objects:

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import *

# Register your models here.

admin.site.register(Airport)

admin.site.register(Flight)

admin.site.register(Passenger)

Then, now, we want to show all passengers on any given flight..

We need to add passenger to the context that we pass to the template. Note that we can do this using the related_name field:

flights/views.py

from django.shortcuts import render

from .models import Flight

def index(request):

return render(request, 'flights/index.html',{

'flights': Flight.objects.all()

})

def flight(request, flight_id):

flight = Flight.objects.get(id=flight_id) # We can also do "pk="

return render(request, 'flights/flight.html', {

'flight': flight,

'passengers': flight.passenger.all()

})

then we update our templates/flights/flight.html

last is to configure our index page:

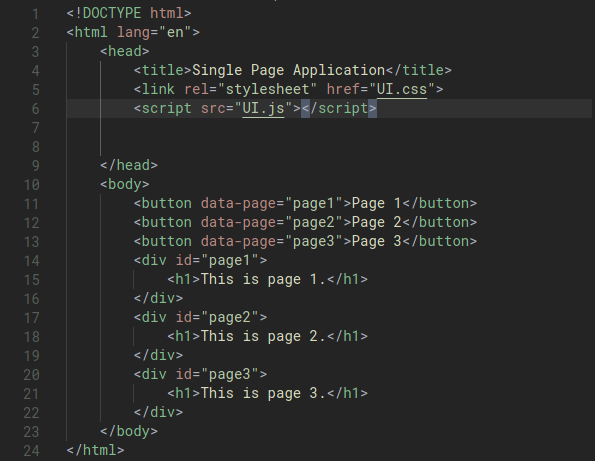

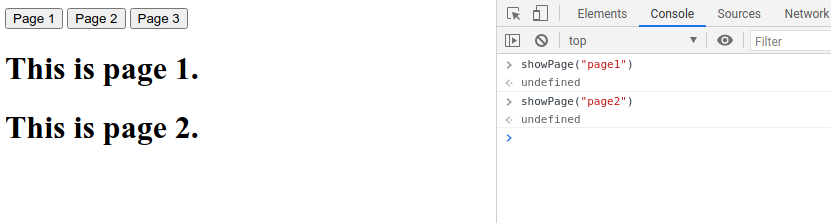

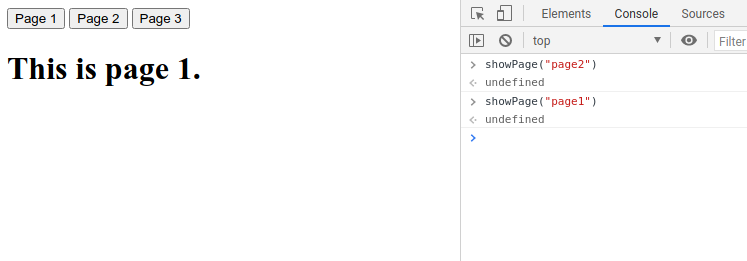

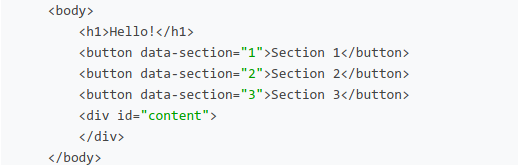

Lecture 5 - JavaScript

General JS

General

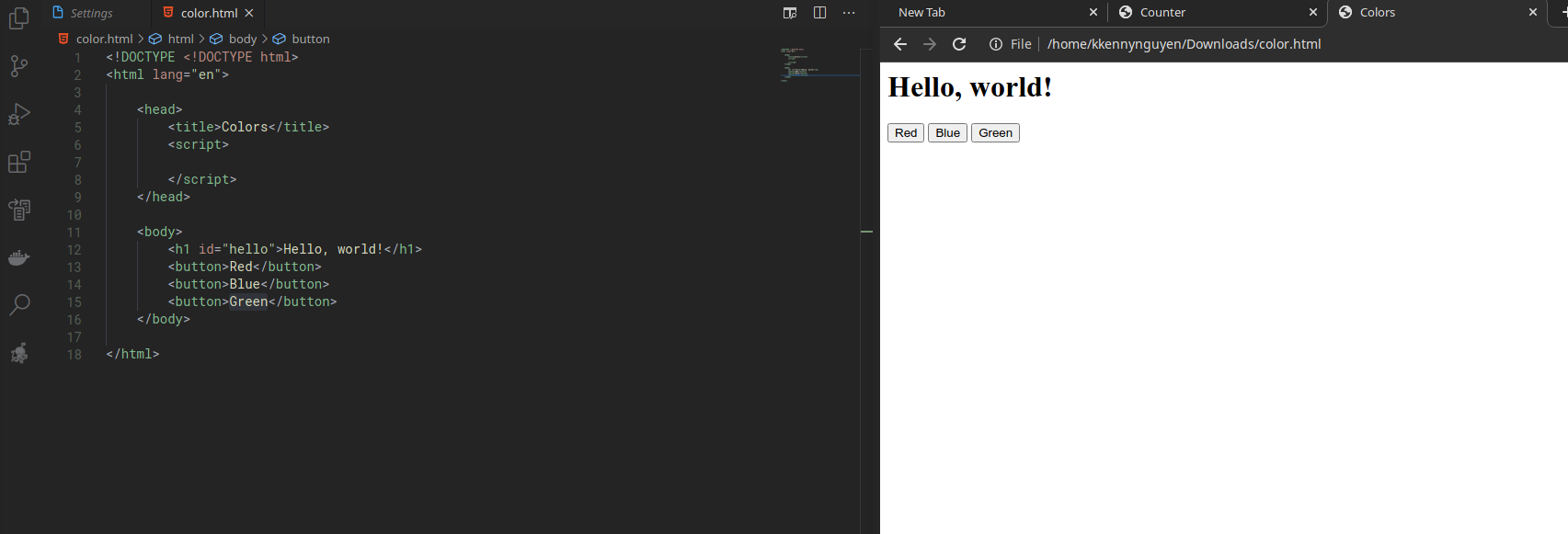

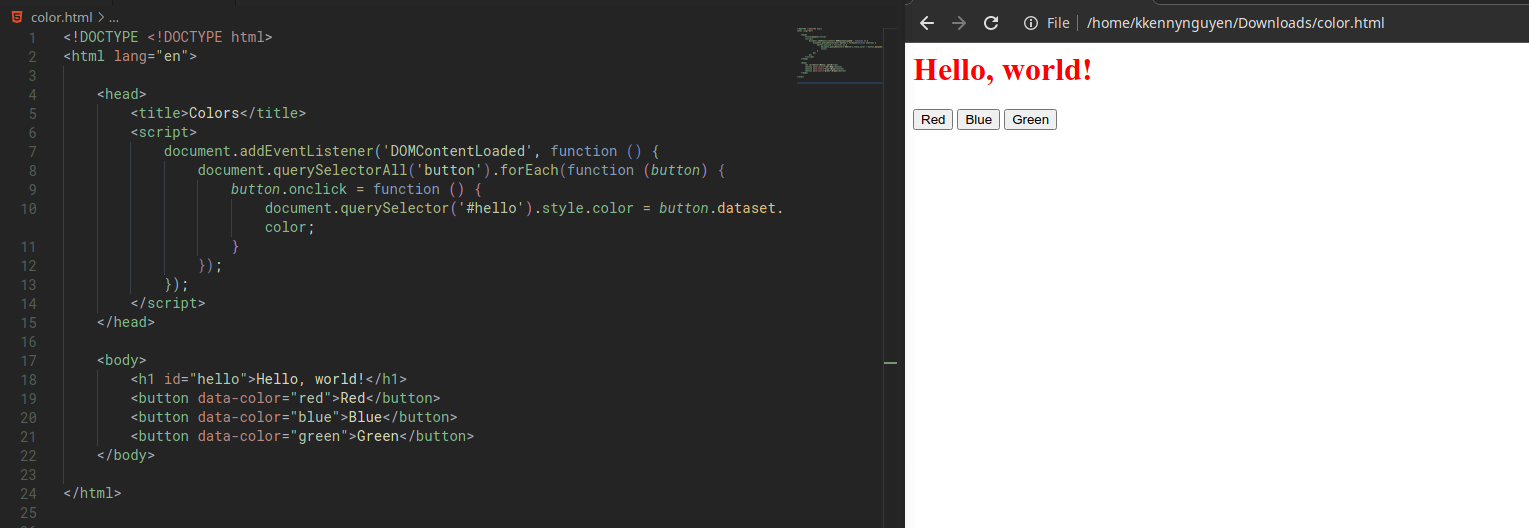

JavaScript enables us to write client-side codes. It enables us to write codes that are run inside the client’s browser application. JS gives us the ability to directly manipulate the DOM, which is the representation of the webpage that the user is looking at. This gives us more power to create an interactive webpage.

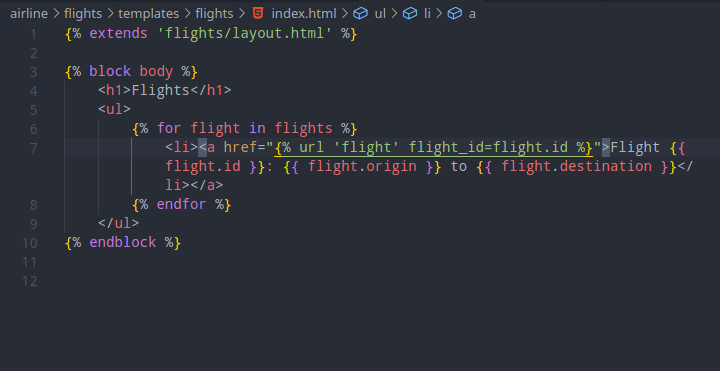

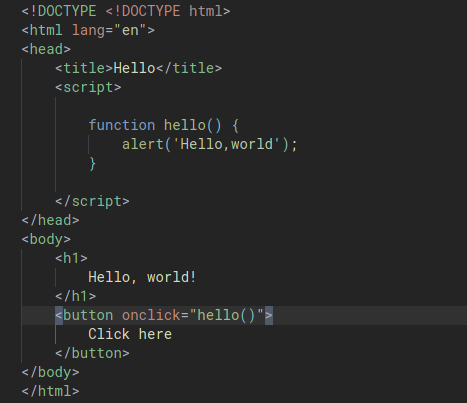

In order for us to enable Javascript in a HTML file, we only need to add some <script></script> tags. These are often located inside the HTML file.

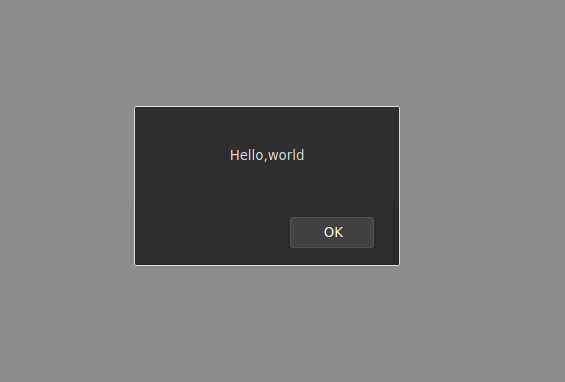

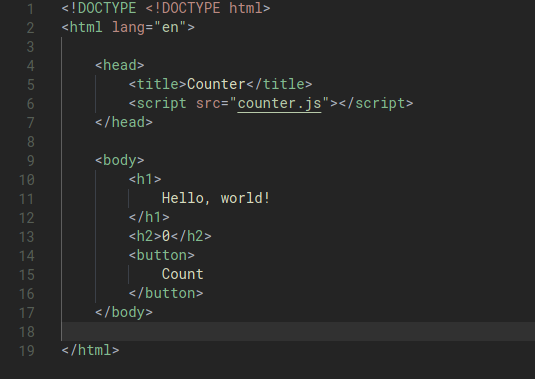

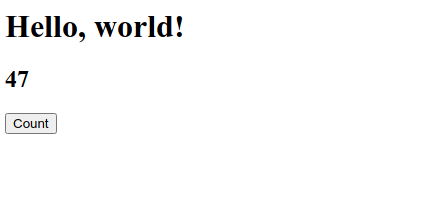

For example, if we have these code:

When we open the the html file, we’d see:

Event-Driven programming

In order to understand the true power of Javascript, we need to understand the concept of event-driven programming, which is a programming paradigm in which the flow of the program is determined by events such as user actions (key presses, mouse clicks, onload, onblur, onmouseover..etc). This is the key dominant paradigm used in graphical user interfacts and web applications.

In an event-driven application, there is generally a main loop that listens for events, then triggers a callback function when one of those events is detected.

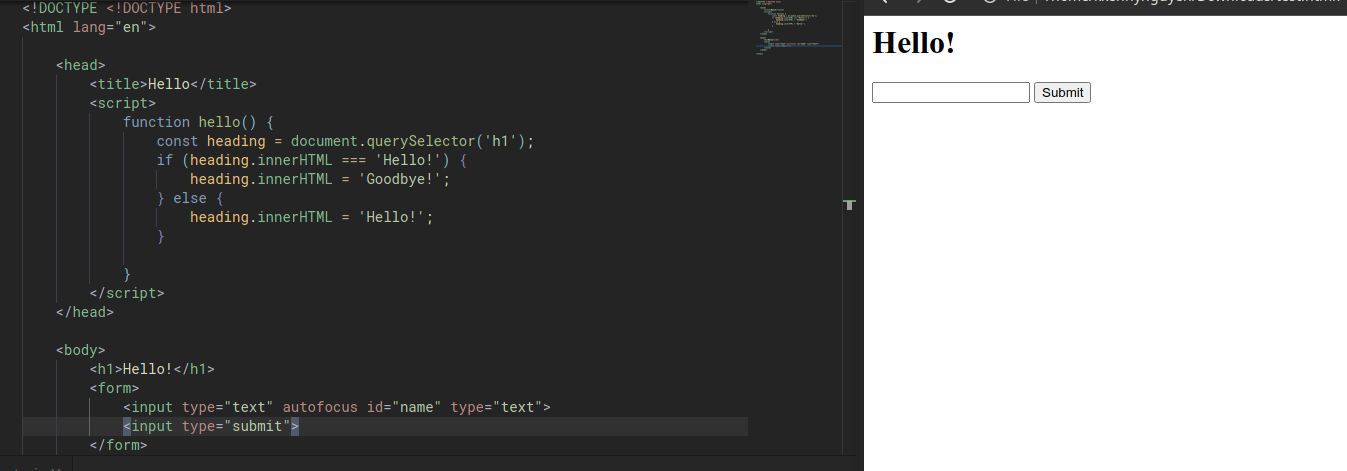

In the below example, we have:

- Created a function

hello()that display the alert when called. - We added a button on our page. We also add an attribute to this button attribute called onclick that adds an onclick handler to the button.

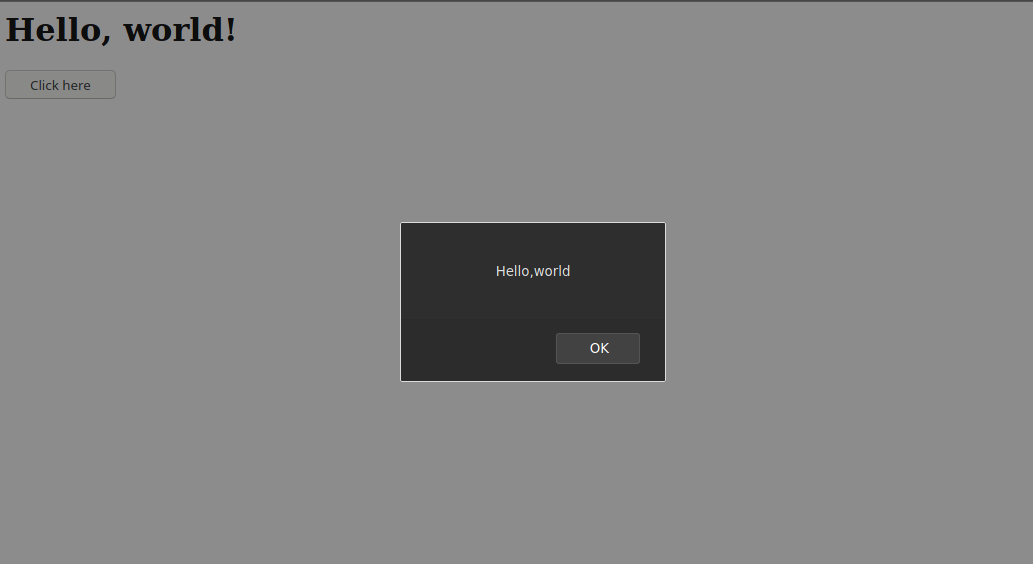

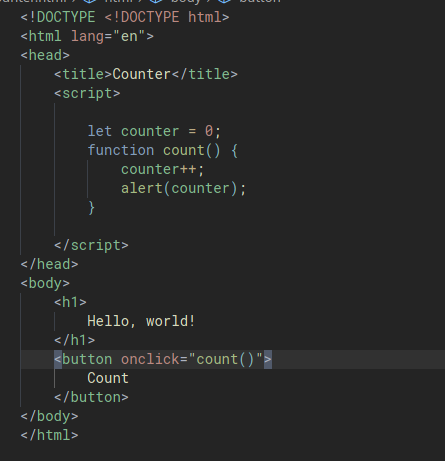

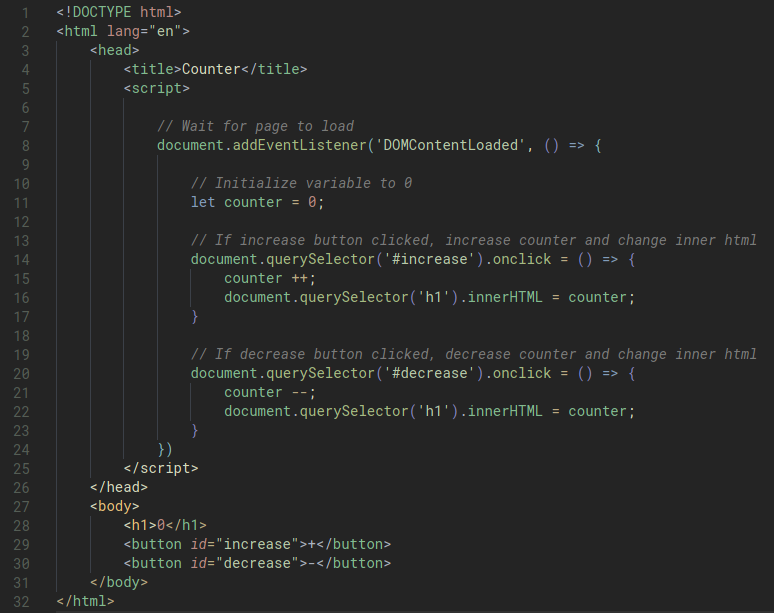

Variables

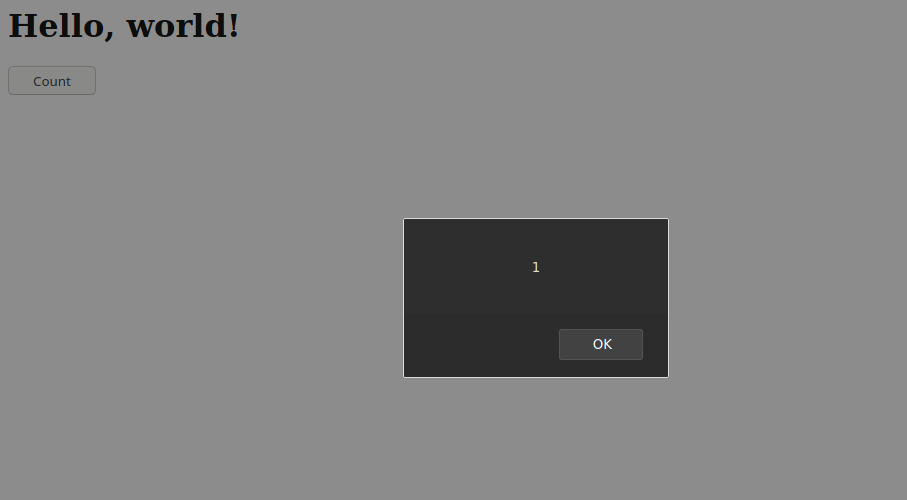

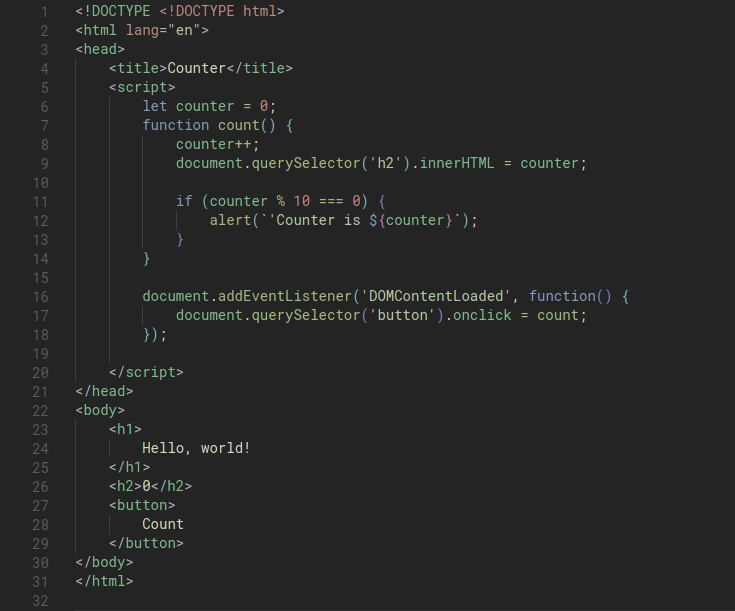

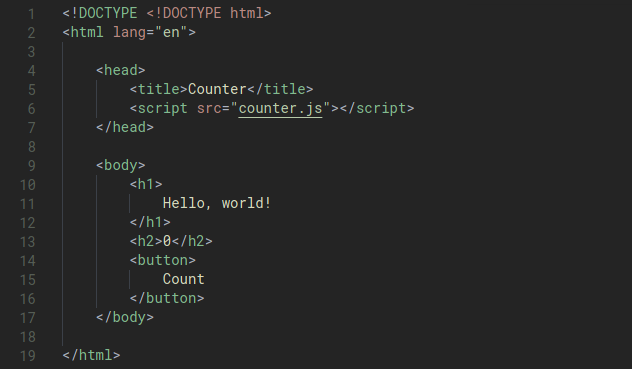

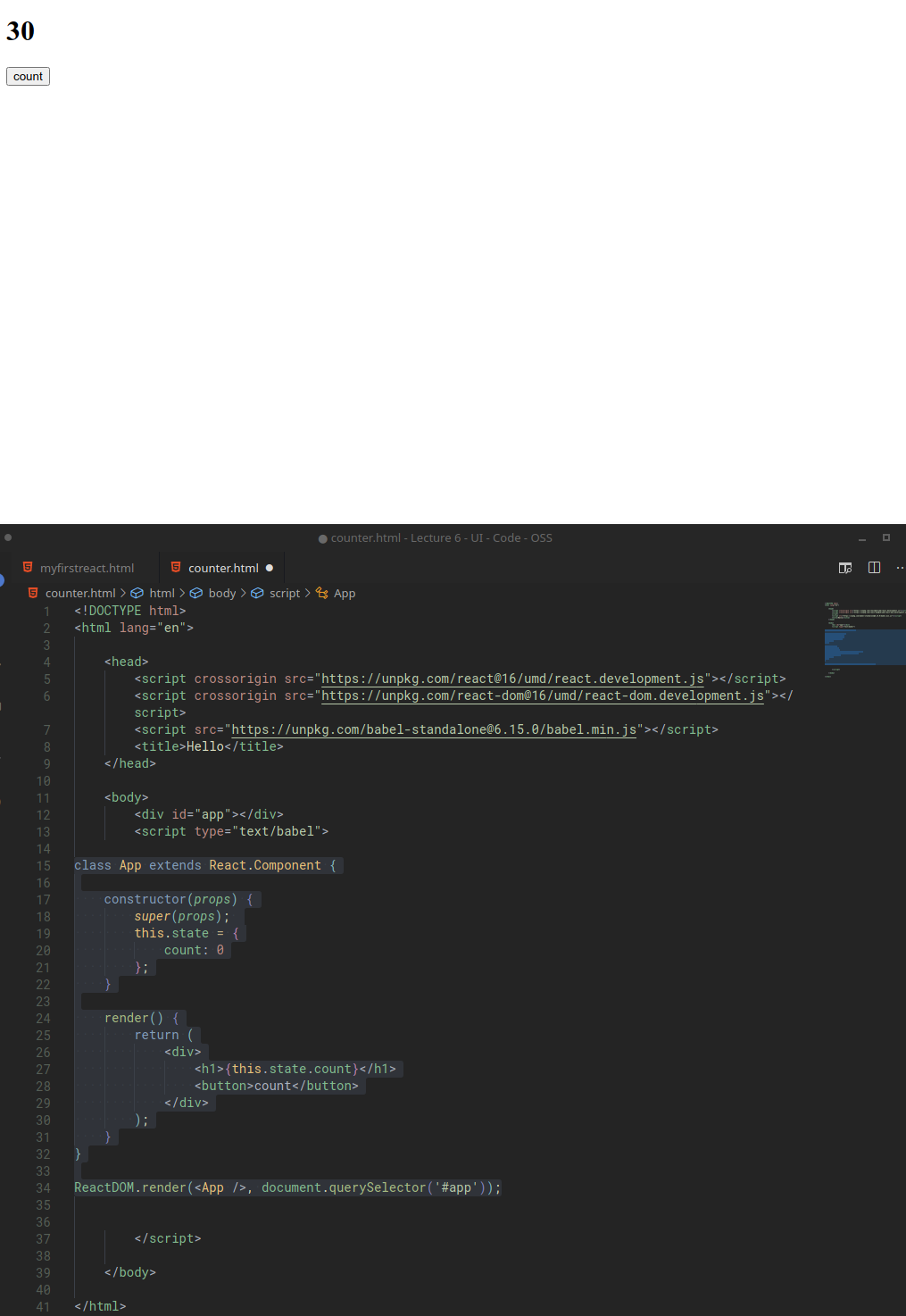

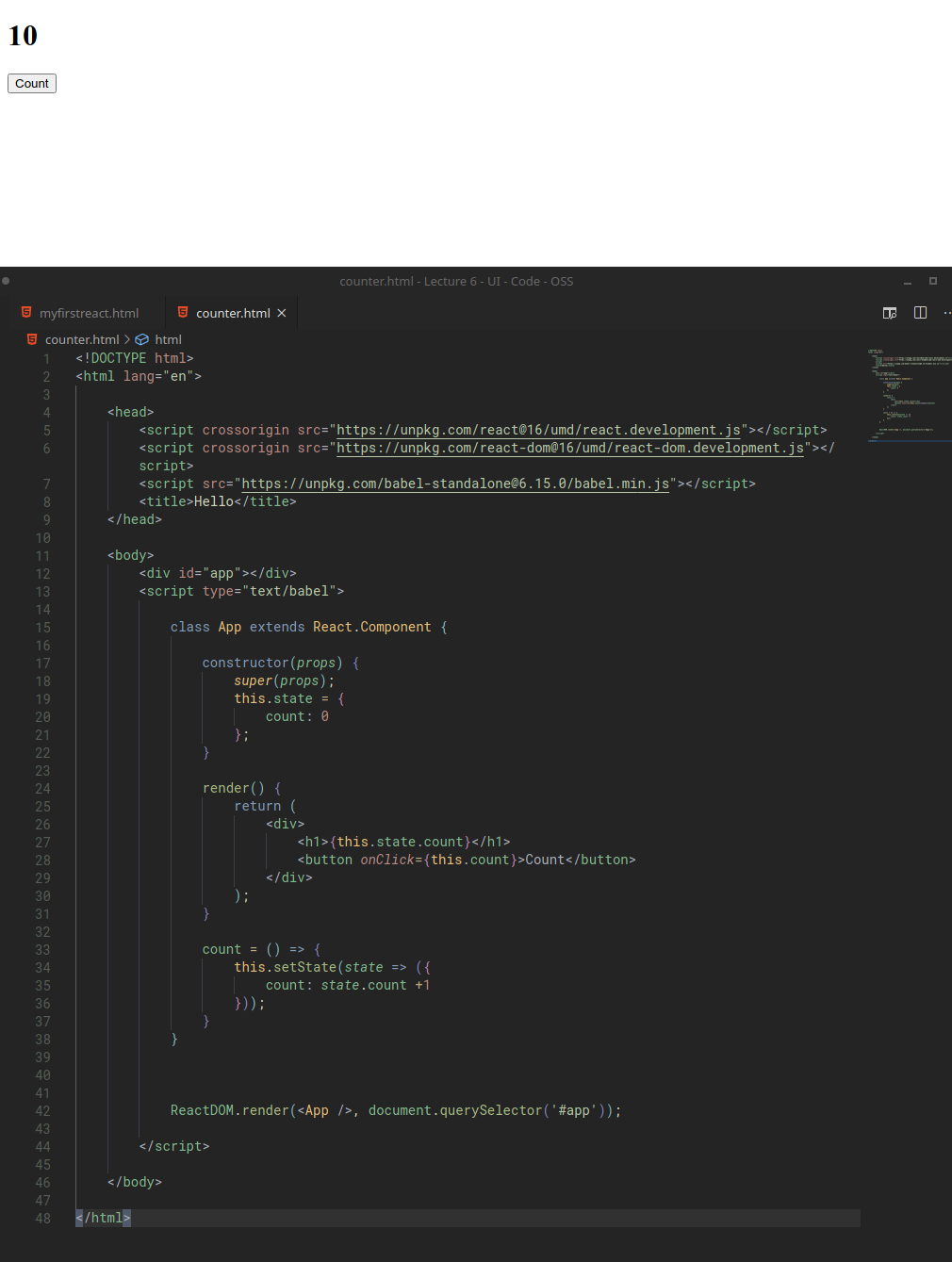

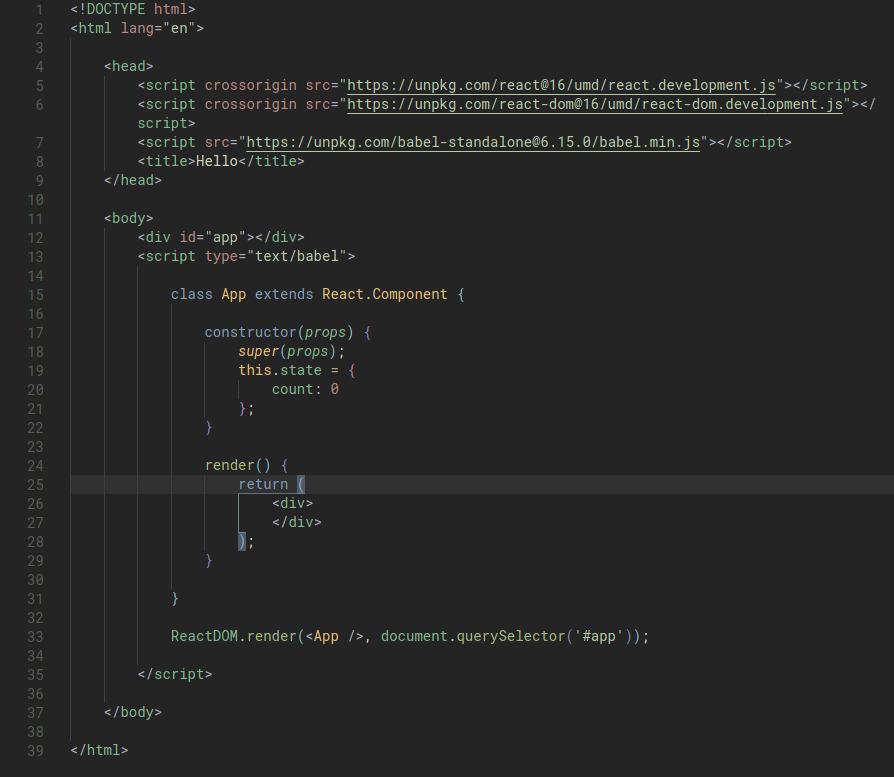

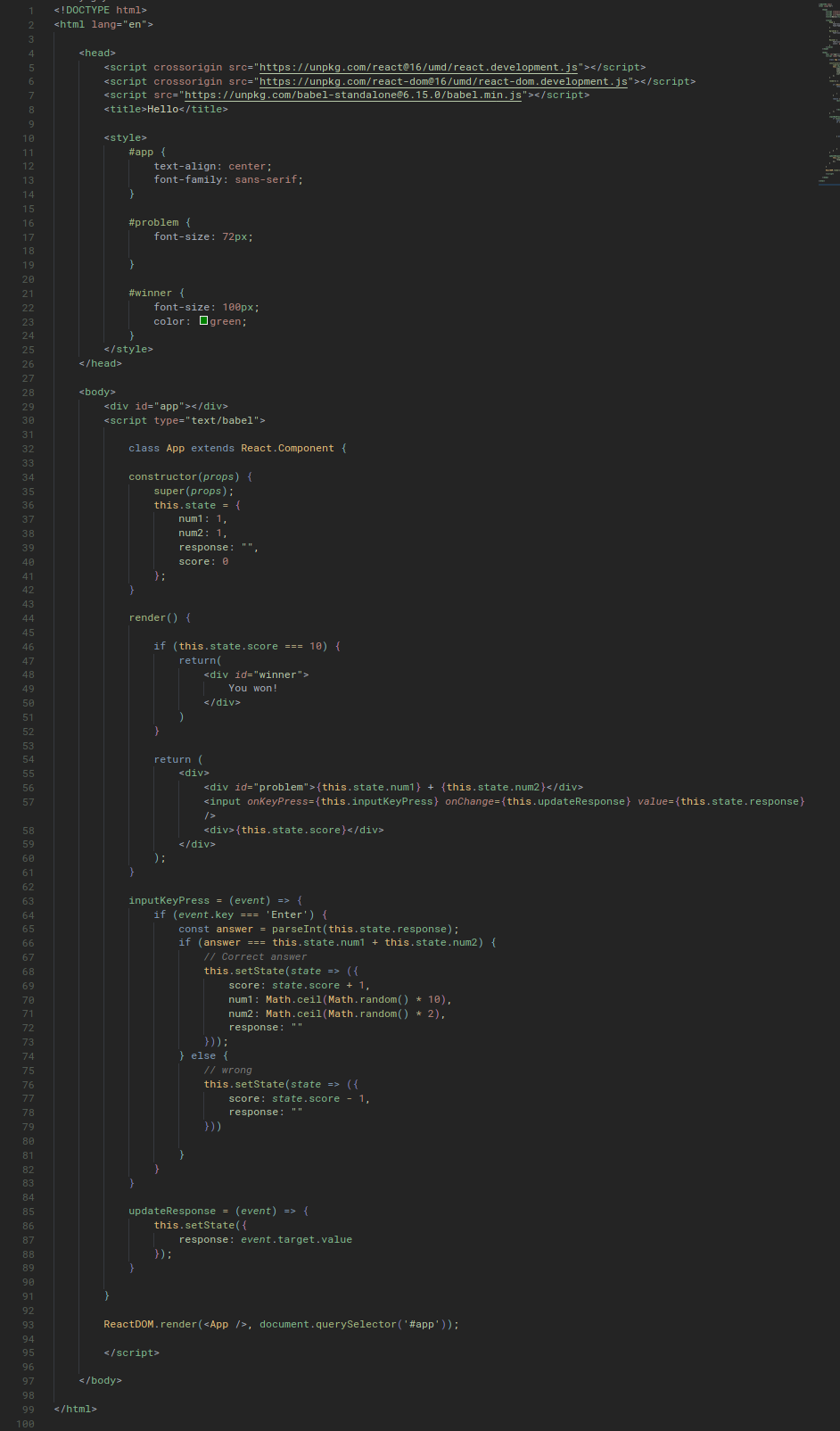

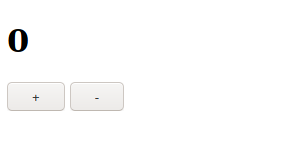

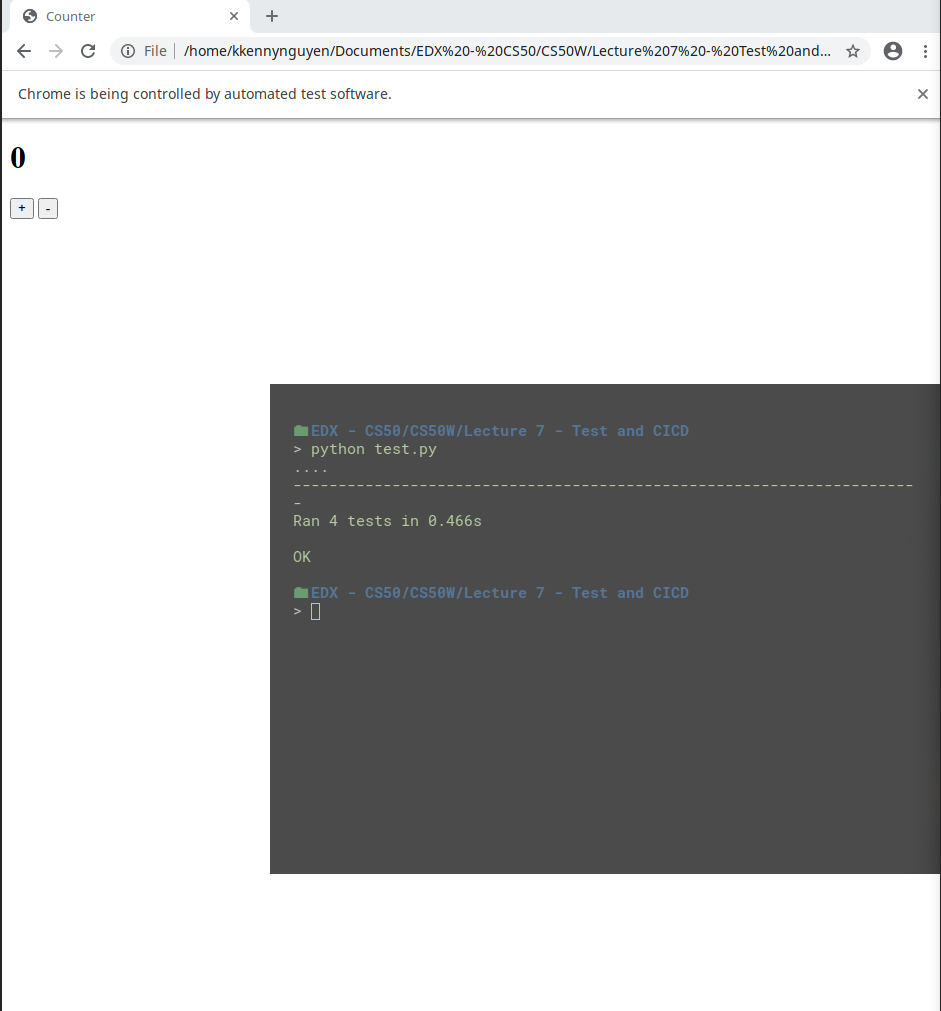

We can create a simple webpage that has a counter function like the below. In this example we use a variable called counter. In this example, we’ll write a simple page that increments the counter variable and display to us the value of this counter.

let vs var

The difference is in scoping rules.

A variable defined using a var statement is known throughout the function it’s defined in, i.e it is scoped to the immediate function body.

A variable defined using a let statement is onlw known through the block it’s defined in, i.e it’s scoped to the imemdiate enclosing block denoted by { }.

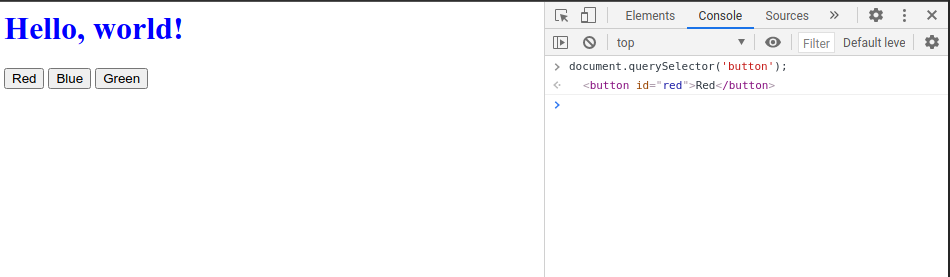

Manipulating the DOM

It would be fairly annoying if the only way that we can interact with the user is by displaying an alert. What would be powerful is if we can update the content of the webpage dynamically by manipulating the DOM.

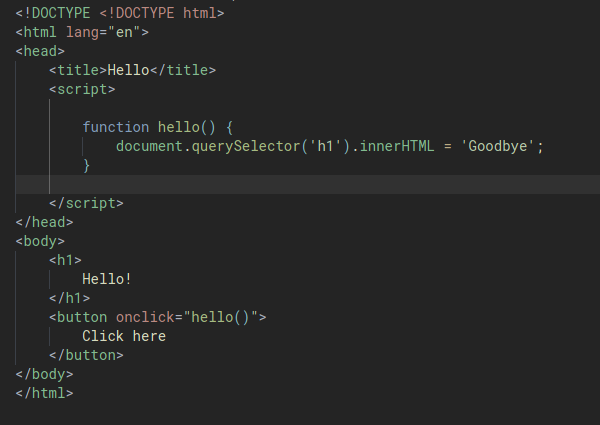

In the below example, we’ll be using a function called document.querySelector() which gives us the ability to look through a HTML document and to extract an element out of it, so that we can manipulate the element with JavaScript. This function only returns one elements so the first matched element will be returned.

We then manipulate the content of the h1 element by using innerHTML to update the inner HTML property to ‘Goodbye’:

When we open the page, it’ll look like this:

After we click on the button:

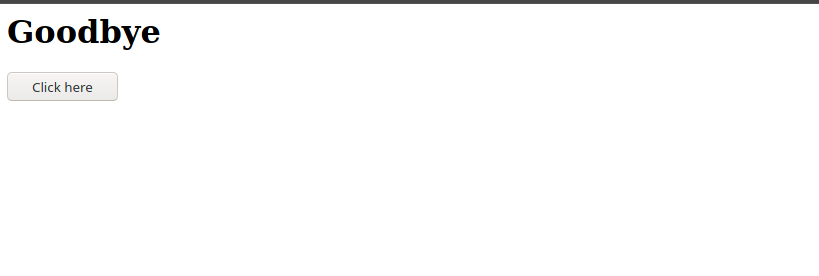

Conditions

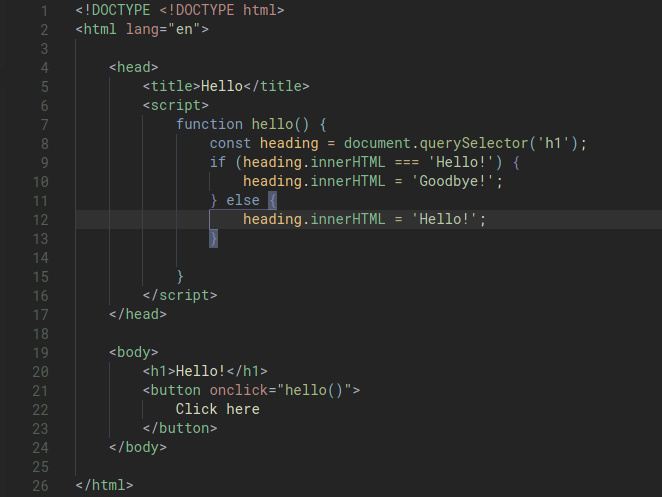

We can also update our code so that the HTML property is “toggled” back and forth using JavaScript conditions.

In JavaScript, we need to use tripple equal (===) to check for strict equality, which means that a property has the same value as well as data type.

function hello() {

const heading = document.querySelector('h1');

if (heading.innerHTML === 'Hello!') {

heading.innerHTML = 'Goodbye!';

} else {

heading.innerHTML = 'Hello!';

}

}

Our code right now looks OK but still a bit clunky because we repeat the document.querySelector() bit three times. We can improve it by storing this value in a variable

If we have a variable that we know we won’t ever be changing, instead of using let we can change it to const. This tell JS that we’ll never be changing the value of the variable to anything else.

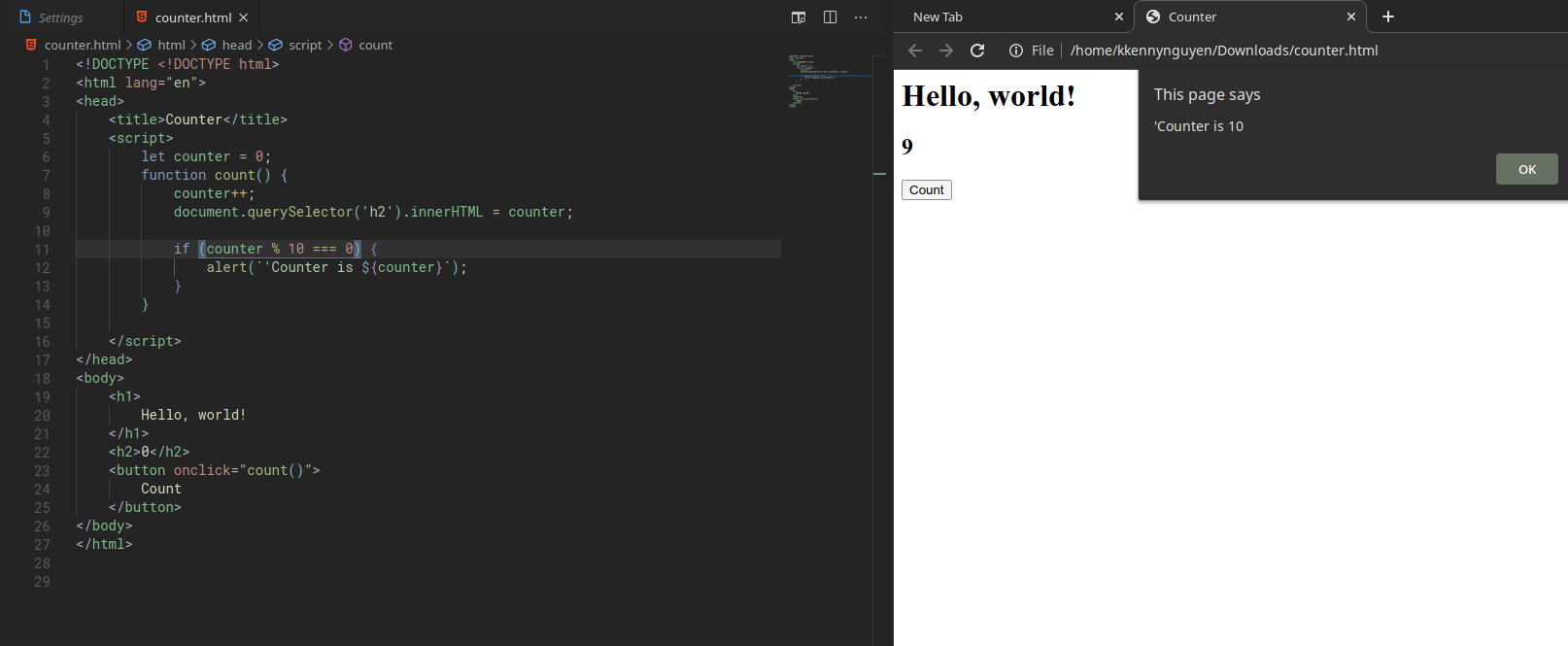

We can update our counter html page so that instead of just displaying the alert, we’ll update the value of a h2 property to display the counter.

We can also fancy up the page by incorporating a logic that displays a message that includes a string and the counter variable when the counter is a multiple of 10.

In order to write a string with a variable/ constant inside it, we wrap the string within two back ticks (```). This is equivalent to the formatted string in Python. The actual variable also needs to be wrapped in curly braces with a dollar sign in front of it.

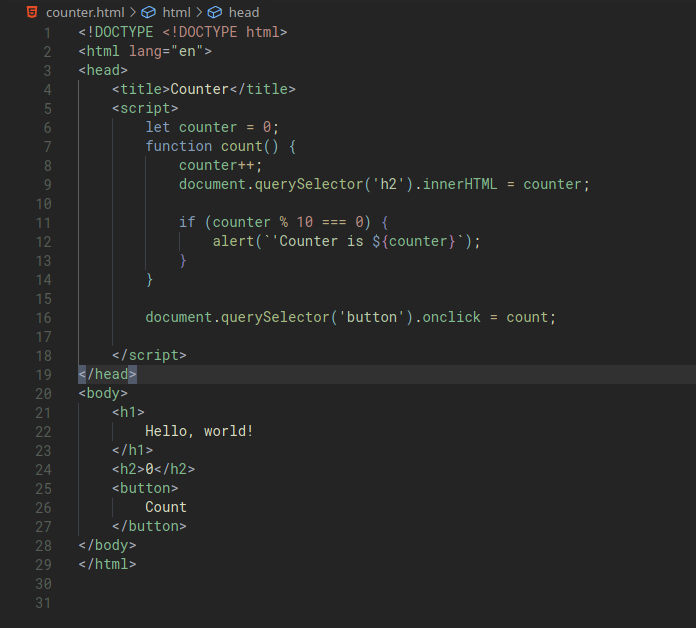

Separating the JavaScript from the HTML using Event Listener

We often don’t want to inter-mingling the content of our HTML and our JavaScript codes. Similarly to how we manage CSS, we often want to separate our JS code from the HTML content of our page.

Instead of hard-coding the onclick property in the button element, we can instead add an event listener inside our script block, like this:

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

/(set the value of the onclick property of the button to count)/

Notice that we are not calling the function and there is no parentheses. We are simply setting onclick to the count function. This way, the count() function is only called, when onclick happens.

The practice of passing functions around in variables like this is the concept of functional programming where we can treat functions like values that can be passed around and manipulated.

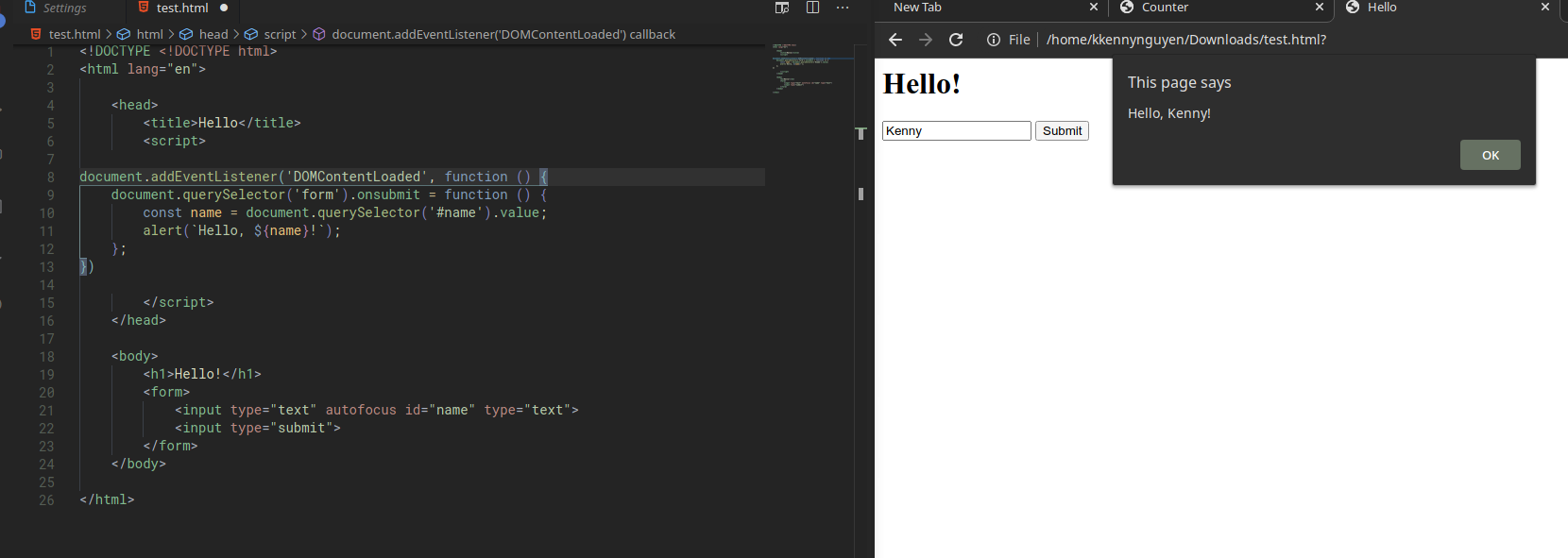

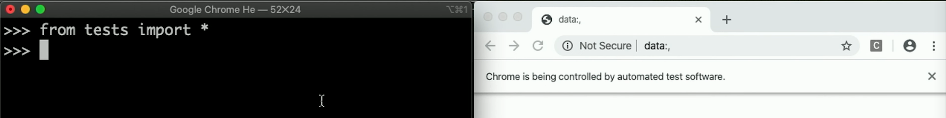

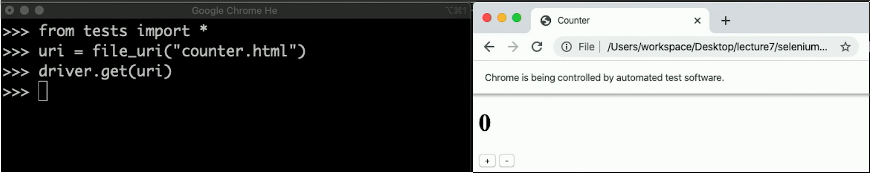

addEventListener() and 'DOMContentLoaded'

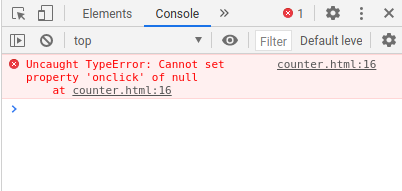

Let’s say we have this:

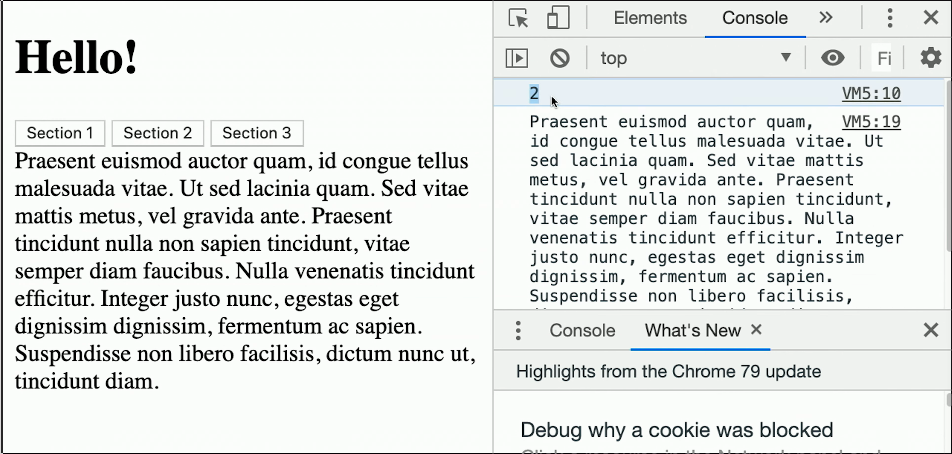

When we open our page and click on the Count button, we’d realise that it does not work and the Count button does not do anything at all. When we run into problems like this, we can inspect the page and look at the Console to investigate the error. For example, if we inspect the console of our counter.html page, we’d see this:

If we look at line 16 of our code:

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

It seems like the Console was telling us that document.querySelector('button') equates to Null. This normally happens when the querySelector function could not find the element.

Why does this happen? It’s because the body of our HTML is read and executed by our browser top-down. When our browser reads line 16, the button element has not appeared yet.

There are a few solutions that we can use:

- Move the script tag to the bottom of the page. or

- Add another event listener to refer to the entire HTML document.

To do this, we’d use the addEventListener() function that takes two arguments.

- The first argument is “what event I want to listen for”, this can be a click, a scroll..etc..

- The second argument is “what function to run after the event happens”.

For our example, we’ll do:

let counter = 0;

function count() {

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

if (counter % 10 === 0) {

alert(`'Counter is ${counter}`);

}

}

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() {

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

});

Note:

- The

'DOMContentLoaded'event is a special event that is only going to be fired or triggered when all the DOM content of the page is done loading. - The

function()is what we call an anonymous function where we don’t want to define a name for the function because it doesn’t need a name, because we don’t need to re-use the funtion. - We can also use the

addEventListenerto set the button onclick to the count function. These two following lines can be used interchangably. They both mean “when the click event happen, run the count function”. The first version is shorter and simpler so we’ll use it instead.document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

document.querySelector('button').addEventListener('click',count);

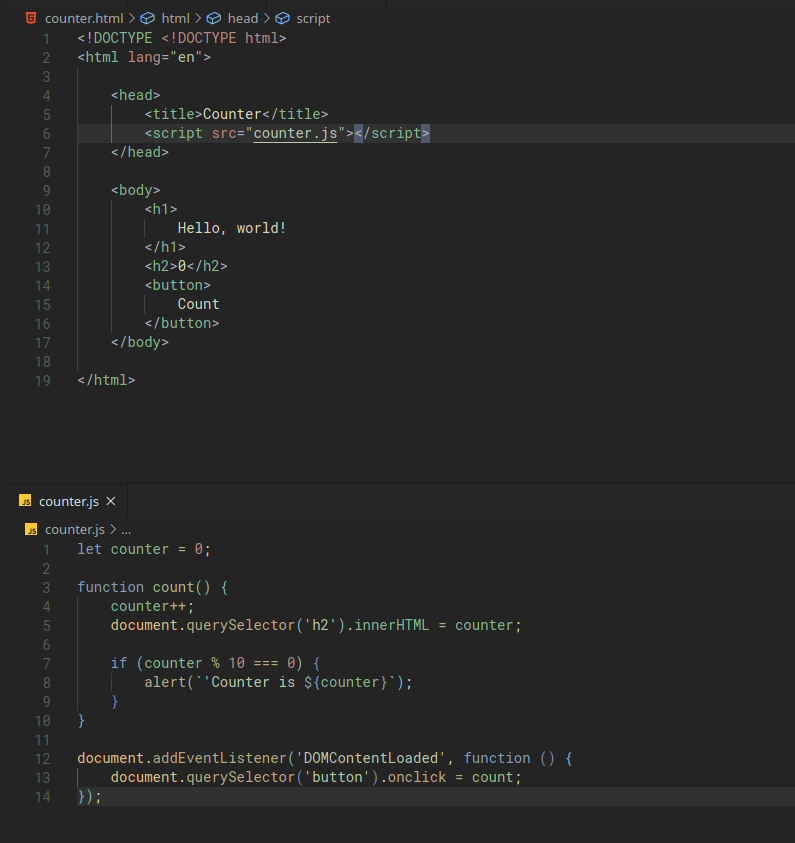

Moving JS into a separate file

The way we do this is very similar to how we put our CSS in a separate file for styling.

- Move all our JavaScript code in a separate file ending in

.js - Add a

srcattribute to the<script>tag that points to this file.

For our counter example, we’d do it like this:

This way out HTML file looks a bit simpler and more readable that the JS codes are separate in a different file.

Another benefits of having our JS separate from our HTML is that we can have multiple HTML files that all share the same JavaScript. We can then have JavaScript libraries that we use for our HTML pages. An example of this is the Bootstrap library.

Slightly advanced JS

Advanced Interactive Page by reading form input

Let’s start making another example of a page that can be more interactive in that the user can interact with a page via a form.

Now, inside of our JS, we’ll remove the hello() function to instead write a simple function that will say Hello to us in an alert box, after we submit our name. The js will look like this. Note that the document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function ().... bit is something that we’ll see very often.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('form').onsubmit = function () {

const name = document.querySelector('#name').value;

alert(`Hello, ${name}!`);

};

})

Note:

- We use

constinstead ofletfor the name variable since we know that we wouldn’t be changing the variable. - We used the

autofocusfield in thenameinput to indicate that the cursor should automatically be set inside the input as soon as the page is loaded. - We use #name inside the

document.querySelector()fucntion to find an element using itsid. We can use the same selector syntax in this function as we could in CSS, to look for specific element in our page. - We can use the

valueattribute of an input field to find what is currently typed in.

Changing the Style of HTML document

Not only that we can change the content of our HTML page, we can also interact with the styles of our page as well.

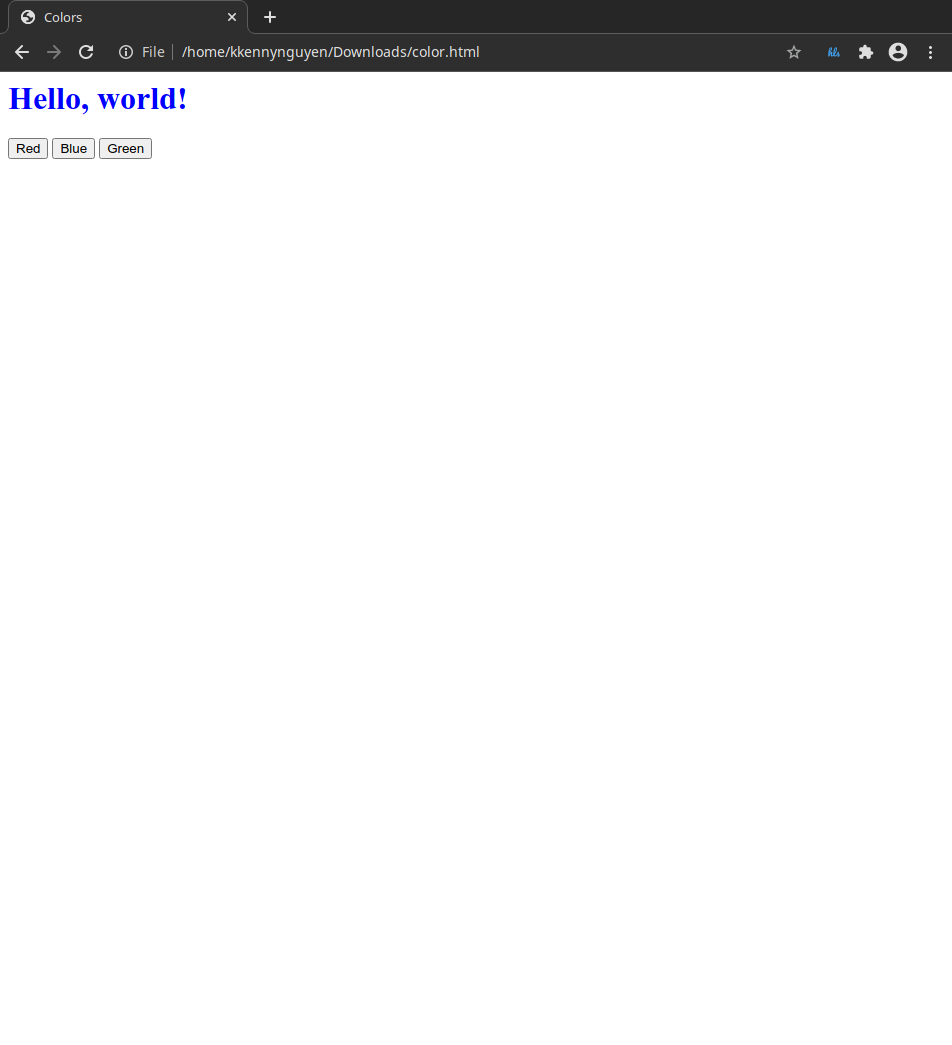

Let’s start with a simple HTML page with three buttons:

Let’s get the button to work by using JavaSript.

First, we need a way to identify these individual buttons. We do this by adding an attribute to each of the button:

<h1 id="hello">Hello, world!</h1>

<button id ="red">Red</button>

<button id ="blue">Blue</button>

<button id ="green">Green</button>

Then, we write out JS:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

// Change font color to red

document.querySelector('#red').onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = 'red';

}

// Change font color to blue

document.querySelector('#blue').onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = 'blue';

}

// Change font color to red

document.querySelector('#green').onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = 'green';

}

})

We’d then have our page with the functional buttons that changes the ‘Hello, world!’ text color.

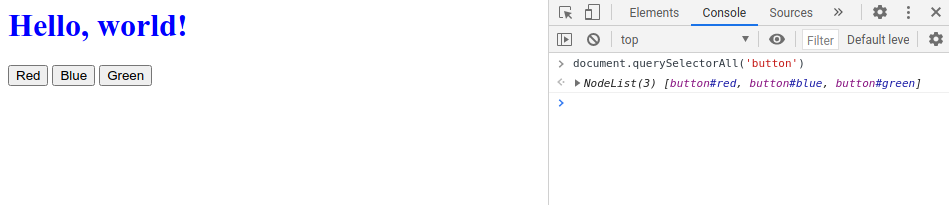

document.querySelectorAll() and forEach()

Our page right now is functional, however the JavaScript text is kind of ugly. Imagine if we have more than three colors, it would be terrible to write.

Moreover, when programming, if we a copy and pasting something, it generally means that there is a better way to do it.

In this scenario, we should think of a way to consolidate our event listener into a single function that handles the color changing. However, if we do it, it’s not clear how the button should change color and what color it should change to.

For that to happen, we need to add an additional attribute to our button. We can use the data attribute. This is how we can associate data with our HTML element.

For our example, we’ll use the data attribute to store the color data that we’ll be using to update our HTML element’s color. So, we’ll update our HTML body to this:

<body>

<h1 id="hello">Hello, world!</h1>

<button data-color="red">Red</button>

<button data-color="blue">Blue</button>

<button data-color="green">Green</button>

</body>

For our JS, instead of using document.querySelector() which only returns a single element that matches our query, we’ll switch to document.querySelectorAll() which will return an array of all elements that match the query.

To demonstrate this, we can actually utilize the console within our web browser, notice how only the first button is picked up:

document.querySelector()

document.querySelectorAll()

/(A NodeList object is a collection of document nodes which is an array-like list of object.)/

/(A NodeList object is a collection of document nodes which is an array-like list of object.)/

Now that we have our list of all the button elements, we’d like to add an event listener that deal with each button individually. We can use a property called forEach(). This function accepts another function as its argument. What it does is: for each of these element, perform this function.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelectorAll('button').forEach(function(button) {

button.onclick = function() {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = button.dataset.color;

}

});

});

Note:

- The anonymous function that we pass to the

forEach()function takes an argument: button. This way we’ll access the individual button as our function iterates through three buttons. - The styling change is done using the

style.SOMETHINGattribute. - Within the buttons, we use

data-SOMETHINGto assign data to the HTML element. These are then accessed by the JavaScript using the element’sdatasetproperty.

Arrow Functions

In recent version of JavaScript, a new notation has been introduced which is the arrow notation for function. This notation allows us to write shorter function syntax

Before:

hello = function() {

return "Hello world!";

}

with arrow function:

hello = () => {

return "Hello world!";

}

If the function has only one statement, we can event do:

hello = () => "Hello world!";

Instead of:

forEach(function (button) {

We can user:

forEach(button => {

In the above example, we have an input (button) which is passed to a function using the arrow notation =>. In cases where we don’t have any input, we can use blank parentheses.

Let’s review the changes:

BEFORE: without arrow notation:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelectorAll('button').forEach(function (button) {

button.onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = button.dataset.color;

}

});

});

AFTER: with arrow notation:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

document.querySelectorAll('button').forEach(button => {

button.onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = button.dataset.color;

}

});

});

BEFORE: without arrow notation:

function count() {

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

if (counter % 10 === 0) {

alert(`'Counter is ${counter}`);

}

}

AFTER: with arrow notation:

count = () => {

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

if (counter % 10 === 0) {

alert(`'Counter is ${counter}`);

}

}

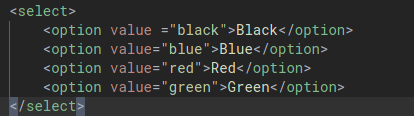

#onchange# event and the #this# value

In the above example, we have been using the onclick event listener which listens to mouse click event, as well as the 'DOMContentLoaded' event when the full DOM has been loaded.

Let’s say we want to change our page, from three buttons to a dropdown list using the <select> tag, like this:

We can use a new event listener called onchange, which apply to things like select drop-down menu. When the user changes their selection, that event will be picked up by the onchange event listener.

BEFORE:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

document.querySelectorAll('button').forEach(button => {

button.onclick = function () {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = button.dataset.color;

}

});

});

AFTER:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

document.querySelector('select').onchange = function() {

document.querySelector('#hello').style.color = this.value;

};

});

Note:

this, in an event listener function, refers to the drop-down menu, which is the element that received the event. In the above example specifically, it means “get the value of the drop-down menu that received the eventonchange”.

There are also many other [[https://www.w3schools.com/js/js_events.asp][events]] that can be used in JavaScript to create an interactive webpage

More about this object

The this object has a special meaning in JavaScript and its meaning varies based on the context where it was used. It is the object that is executing the current function.

In a method, this refers to the owner object.

Alone, this refers to the global object.

In a function, this refers to the global object.

In a function in strict mode, this is undefined.

In an event, this refers to the element that received the event.

Methods like call() and apply() can refer this to any object.

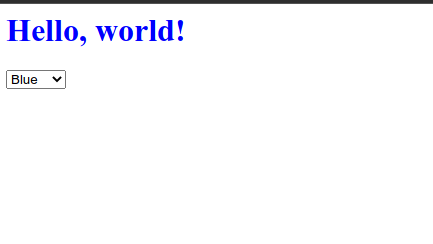

Building a TODO List

In the Django lesson, we built a TODO list with a webserver logic, however, we can actually build one with just javascript.

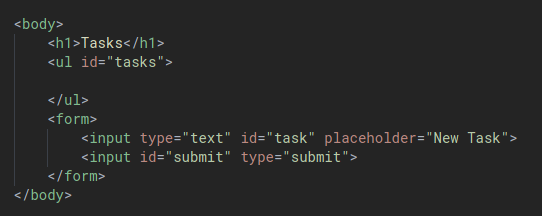

Let’s start with a simple HTML:

Technically, we have an unordered list within our page, however there is nothing in it yet.

Handling the Submit input

Let’s add some JavaScript so that we can actually have a working Submit button. We’d like it to do something, when the user hits the Submit button.

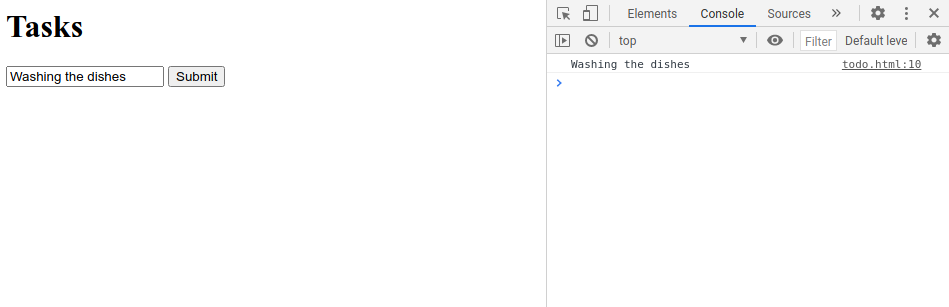

Before we do this, let’s try to instead print out the Task input first by using the console.log() function that will print out the value onto the console. This is an approach that we can use to debug our program.

In the below code, we have also added return false. We want our form to stop from submit so that everything that happens is retained within the browser.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('form').onsubmit = () => {

const task = document.querySelector('#task').value;

console.log(task);

// Stop form from submitting

return false;

}

});

However, this is not all that we want. What we are wanting to happen is to add an element into the <ul> tag. This item will be wrapped in <li>.

This is how we do it:

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('form').onsubmit = () => {

const task = document.querySelector('#task').value;

const li = document.createElement('li');

li.innerHTML = task;

document.querySelector('#tasks').append(li);

document.querySelector('#task').value = '';

// Stop form from submitting

return false;

}

});

Note:

- We create a new element

'li'bycreateElement()and then fill its innerHTML with thetaskvariable. The addition of this new element to the unordered list is done using theappend()method. - We clear out the task input text field so that the text is not retained after user has submited the data.

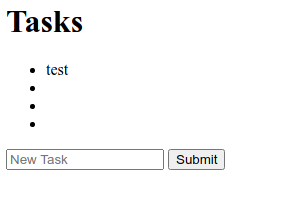

However, we’ll have a small bug at this point, even if the user hits the submit button when the text field is empty, that empty string would still be added to the list:

What we want to do is to disable the submit button until the user has actually typed something into the text field. We can do this by JavaScript. To do this, we’d also need to id our submit button:

For this, we’ll also be using a new event called onkeyup. This is when the user a key is lifted up from the keyboard.

We also need to add a few logic including:

- If the input field is empty, submit button should be disabled.

- After user add a new task, submit button should be disabled.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

// By default, submit button should be disabled

document.querySelector('#submit').disabled = true;

// on keyup event from input #task, submit button should be enabled

// if the task input field isn't empty

document.querySelector('#task').onkeyup = () => {

if (document.querySelector('#task').value.length > 0) {

document.querySelector('#submit').disabled = false;

} else {

document.querySelector('#submit').disabled = true;

}

};

document.querySelector('form').onsubmit = () => {

// Hold on the user input

const task = document.querySelector('#task').value;

// Create new li element with user input as inner HTML

const li = document.createElement('li');

li.innerHTML = task;

// Add new element to unordered list tasks

document.querySelector('#tasks').append(li);

// Clear out the task input text field

document.querySelector('#task').value = '';

// after task is added, disable the submit button

document.querySelector('#submit').disabled = true;

// Stop form from submitting

return false;

}

});

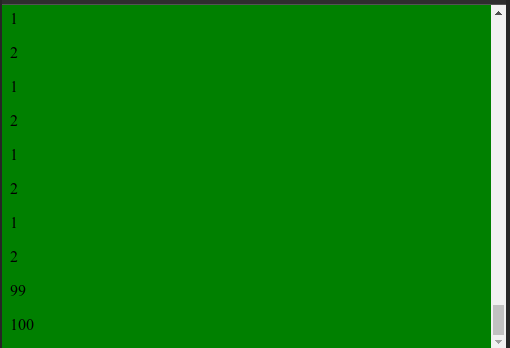

Intervals

In addition to dealing with events that are triggered by users, we can also set functions to run after a set amount of time.

For example, let’s return to our counter page an add an interval tso that even if the user doesn’t click on anything, the counter increments every second.

For this, we’ll use the setInterval() function. In it, the first argument is the function to be run, and the second argument is the time (in miliseconds).

This is our HTML:

This is our js:

let counter = 0;

count = () => {

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

}

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

setInterval(count,1000);

});

The count function will run on itself:

Local Storage

So far, all the information on our pages are lost when we reload the page. This is because JavaScript does not return any information about your browser session.

In the counter example above, when we reload the page, the counter would go back to zero. A lot of the times this is intended, however sometimes we’ll want to be able to store information that we can use when a user returns to the site later.

This can be done using Local Storage. It allows us to store information inside of our web browser that can be accessed later. This information is stored as a set of key-value pairs, almost like a dictionary.

Two key functions that we’ll need to utilize are:

localStorage.getItem(key)searches for an entry in local storage with a given key, return the values associated with that key.localStorage.setItem(key, value)sets an entry in local storage by associating the key with a new value.

Let’s employ this to retain our counter value.

Here is our HTML:

BEFORE:

let counter = 0;

count = () => {

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

if (counter % 10 === 0) {

alert(`'Counter is ${counter}`);

}

}

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

setInterval(count,1000);

});

AFTER:

if (!localStorage.getItem('counter')) {

localStorage.setItem('counter', 0);

};

count = () => {

let counter = localStorage.getItem('counter');

counter++;

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = counter;

localStorage.setItem('counter', counter);

}

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function () {

document.querySelector('h2').innerHTML = localStorage.getItem('counter');

document.querySelector('button').onclick = count;

});

Now, our counter value is retained on the page.

APIs Introduction

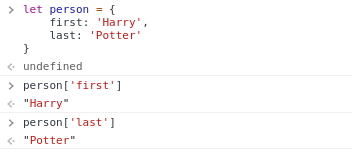

One of the most useful datatype inside JavaScript is JavaScript Object. A JavaScript object is very similar to a Python dictionary as it also allows us to store key-value pairs.

Example:

let person = {

first: 'Harry',

last: 'Potter',

}

One way in which JavaScript Objects are really useful is in transferring data from one site to another, particularly when using APIs. APIs, in the context of web application are structured form communication between two different applciations.

APIs are used to transfer data between two applications using a well-structured format. This format happens to be JSON, which stands for JavaScript Objects Notation.

Example:

{

"origin": {

"city": "New York",

"code": "JFK"

},

"destination": {

"city": "London",

"code": "LHR"

},

"duration": 415

}

JSON offers a very convenient representation of data that can be used for writing and consuming APIs.

JSON standard requires *double quotes* and does not accept single quotes.

Currency Exchange

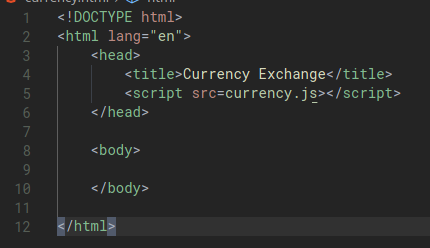

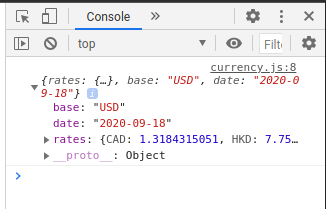

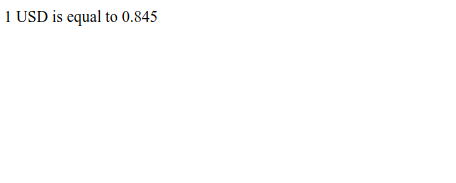

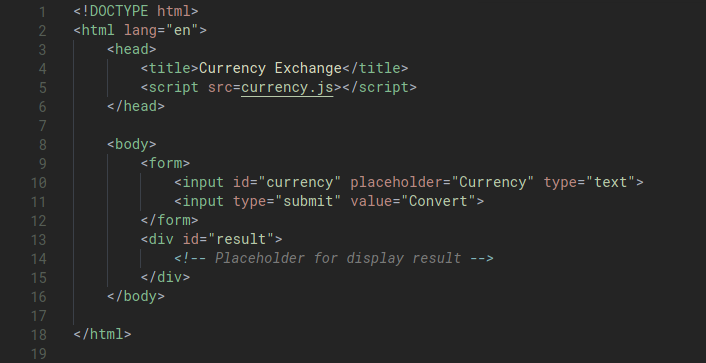

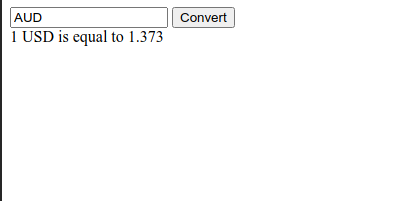

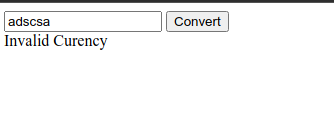

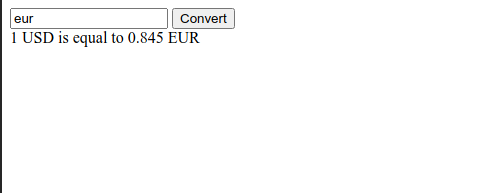

Intro & fetching the data asynchronously

Let’s work on building an application where we can find exchange rates between two currencies. For this example, we’ll be using the European Central Bank’s Exchange Rate API (https://exchangeratesapi.io/). By visting their website, we can see the API documentation which shows us how to use the API.

For example, we can visit https://api.exchangeratesapi.io/latest?base=USD to see exchange rates with base = USD:

{

"rates": {

"CAD": 1.3184315051,

"HKD": 7.7501056368,

...