CS50's Introduction to Computer Science

Week 0 - Computational Thinking, Scratch

What is Computer Science?

It’s just the process of solving problems.

We have some input and we want an output. What’s happening in the middle is computer science.

However, when we start to look into problems from the get-go. The first important step that we need to think about is how to represent the information on the computer. Unlike the human world where there are 9 digits, as well as different letters and symbols, computer only speaks in two digits - ones and zeros.

Representing information on the computer

Let’s take a look at an example of how numbers are represented in the human brain and in the computer brain:

- When we look at the number 123. What we instintively identify this through years of learning is the number: one hundred and twenty three. This is the end product of the mental image that we normally take for granted. We don’t really think about how we come up with this number. However if we break it down, we get to this end product by thinking in a system that we have grown accustomed to over the year. We have 10 digits (zero to nine). As such, in order to process numbers that are greater than 9, we have to teach our brain to think in the powers of 10. As soon as we surpass 9, we step into the world of two-digit and as such the rightmost integer goes back into zero whereas the leftmost integer turns into one.

| 10^2 | 10^1 | 10^0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Human Number | Value in powers of 10 |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10^0 |

| 10 | 10^1 |

| 100 | 10^2 |

| 1000 | 10^3 |

| 10000 | 10^4 |

i.e: When we have one digit, we can process upto but not including number 10 (10^1). When we have two digits, we can process upto but not including 100(10^2).. and so on..

- On the computer, we only have zero and one. Therefore we would also have to design a system that can process numbers (as well as characters) that are other than zero and one. Turns out this idea is somewhat similar to the way we think about numbers. However

- If we have one bit, we can only process number up to, but not including two (2^1).

- If we have two bit, we can then process number up to, but not including four (2^2).

- When we have three bit, we can then process number upto, but not including eight (2^3).

| Computer Number | Numerical value in power of 2 |

|---|---|

| 0 0 0 1 | 2^0 |

| 0 0 1 0 | 2^1 |

| 0 1 0 0 | 2^2 |

| 1 0 0 0 | 2^3 |

| 1 0 0 0 0 | 2^4 |

| 1 0 0 0 0 0 | 2^5 |

Let’s try turning a few numerical numbers into binary values:

- How do we represent the number 50 in binary?

Ok so we have

[64][32][16][8][4][2][1]. 64 is 2^6 so we know that we don’t need the seventh bits. We need six. So now we know that our binary representation has six bits. We then take away the leftmost bit which is 32. We do this by switching the leftmost bit to 1. Ok so now we have1 0 0 0 0 0, which is representation of number 32. 50 minus 32 is 18, so we need to take away 18 more. The next biggest number is 16, so we take away the next bit. Now we have1 1 0 0 0 0, which is the representation of 48. We now have only two left. So we only need to take away the second bit (2). And the result is1 1 0 0 1 0.

Byte

That’s the very basis of computer binary language. However we all know that when we think about how computer represent single characters, it’s not in one, or two bits but actually 8 bits. This is one byte.

We know that numbers aren’t everything that are represented on the computer but also letters are other stuff. Therefore all we need is to come up with a system that assign letter “symbols” to numbers so that our computer can understand a letter when they are provided with a number. Thus we agree that letter A is number 65, in the context of word-processing.

Therefore, letter A, in binary values, represented by a byte is: 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1. The aforementioned system is the famous ASCII. The system is American-biased however. Unicode is then born which is the superset of ASCII. Unicode is also the system that engines the emoji.

..This is only the beginning. A few hundred years ago we humans also come up with a system to represent colours, which is the RGB system. Which is pretty much a three-value system to represent colours. A single pixel can range from [0 0 0] which is black, to [255 255 255], which is white. We can now easily tell that a single pixel is consisted of three bytes which is 24 bits. Black and White images consist of 8 bit because the colours only range from white to black.

To wrap it up, all of the information that is represented on the computer come down to ones and zeroes.

Algorithm

Now that we are able to represent information on the computer i.e having the input. How do we get our output? What’s in the box in the middle?

By algorithm, which is the basis of Computer Science. An algorithm is just a step-by-step instructions that we use to tell the computers how to process out input to get the desired output.

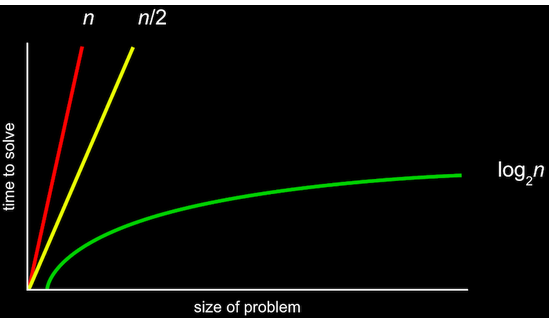

A human example of algorithm is finding a contact in the phone book. An inefficient algorithm would be to turn the pages one-by-one to find someone with last name starting with S using the phonebook. A better one is to turn the pages two-by-two. A better algorithm would be to cut the phonebook into half and do it again until we are closer to the S part. This is basically the divice and conquer method.

What we just compared are two algorithms. Turning one-by-one page can be represented n and divide and conquer is log(n) where n is the size of the problem. There is fundamentally a big difference between these two.

Supposedly, if the book has 1024 (2^ 10) page, it would take us 10 steps to get to the page if we strictly keep on divide and conquer. The pseucode code for this algorithm would be:

Pick up phone book Open to the middle of phone book Look at Page If Adam Smith is on page Call Adam Else if Adam Smith is ealier in book Open to middle of left half Back to line 3 Else if Adam Smith is later in book Open to middle of right half Back to line 3

What are the bolded bit? They are functions. The other bits can easily be spotted - Boolean expressions conditions and loops. These are the very basic concept of programming. There are also more advanced concepts like events, threads, variables, operators..etc..

Essentially, all of our problems can fit into the same model of input -> algorithm -> output.

Week 1 - C

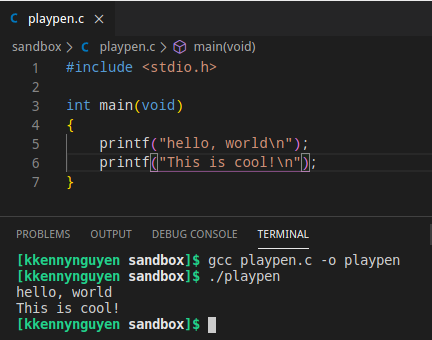

hello, world

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("hello, world\n");

}

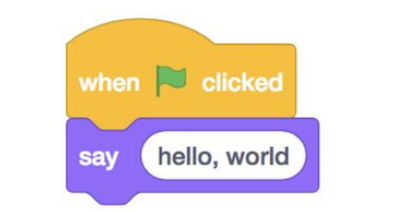

The above script can be illustrated as per illustration below that is in Scratch:

Breakdown:

- The ‘when green flag clicked’ block in Scratch basically starts the main program. In C, the first line for the same is

int main(void). - In C, strings are encapsulated in double quotes.

- In C, we finish our line of code with a semicolon

; - The header line on the top means somewhere on our computer there is a file named

stdio.hthat includes the code that allow us to access and use theprintffunction. Theincludeline tells the computer that our script will need the computer to include that file when it’s ran. Without that line, the computer would not understand how to do theprintffunction. .cis the file extension for source code files that that are written in C/C++

#+begin_center

#+end_center

#+end_center

Computers don’t understand English, or even the C programming language. Therefore we need to convert the source code files into binary instructions which are understood by the computer. The tool which we can use is called the compiler.

#+begin_center C language source code ==> [compiler] ==> machine-language binary file #+end_center

taking input

Let’s try to do this:

We try this by:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

string answer = get_string("What's your name?\n");

printf("Hello, %s\n", name);

}

The %s is the dynamic placeholder of type string that we use to inesrt the variable answer into the printed line.

The printf function is one that takes from zero to many arguments. In the above example, we passed two arguments.

If we go on to compile the file, we’d get a bunch of errors. This is normal. A lot of the times, a single mistake can lead to many errors because the compiler would then starts intepreting correct code incorrectly and generates more “phantom errors”.

We should jump to the very first error:

input.c: In function ‘main’:

input.c:5:5: error: unknown type name ‘string’; did you mean ‘stdin’?

5 | string answer = get_string("What's your name?\n");

| ^`

| stdin

The error was unhelpful because in this example we actually meant to want a string, not stdin.

To get around this we have to import a training wheel library that CS50 has created. I installled this from yay.

Then I need to add one more include line to reference the newly downloaded library.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <cs50.h>

int main(void)

{

string name = get_string("What's your name?\n");

printf("Hello, %s\n", name);

}

I tried compiling but still got errors:

$ gcc input.c -o input

/usr/bin/ld: /tmp/cc10JjiR.o: in function `main':

input.c:(.text+0x1a): undefined reference to `get_string'

collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

This means the computer did not understand what get_string means. It turns out that in C, albeit a little bit redundant, we also have to tell our compiler to add the special CS50 library.

$ gcc input.c -o input -lcs50

$ ./input

What's your name?

Kenny

Hello, Kenny

We can also use the make utility to compile our C program.

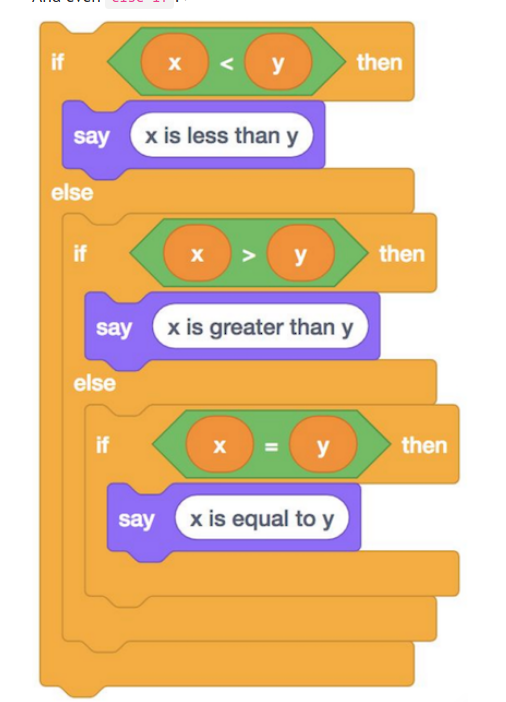

Dealing with conditions and variable

Let’s try doing this in C:

In C, conditions are not ended with semicolons.

Because the single = is used as the assignment operator, we need to use == to compare two values.

{

int x = 1;

int y = 2;

if ( x < y)

{

printf("x is less than y\n");

}

}

The basic for loop

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 50; i++)

{

printf("Hello, world - run %d\n",i + 1);

}

}

$ gcc forloop.c -o forloop

$ ./forloop

Hello, world - run 1

Hello, world - run 2

Hello, world - run 3

Hello, world - run 4

Hello, world - run 5

Hello, world - run 6

Hello, world - run 7

Hello, world - run 8

Hello, world - run 9

Hello, world - run 10

Hello, world - run 11

Hello, world - run 12

Hello, world - run 13

Hello, world - run 14

Hello, world - run 15

Hello, world - run 16

Hello, world - run 17

Hello, world - run 18

Hello, world - run 19

Hello, world - run 20

Hello, world - run 21

Hello, world - run 22

Hello, world - run 23

Hello, world - run 24

Hello, world - run 25

Hello, world - run 26

Hello, world - run 27

Hello, world - run 28

Hello, world - run 29

Hello, world - run 30

Hello, world - run 31

Hello, world - run 32

Hello, world - run 33

Hello, world - run 34

Hello, world - run 35

Hello, world - run 36

Hello, world - run 37

Hello, world - run 38

Hello, world - run 39

Hello, world - run 40

Hello, world - run 41

Hello, world - run 42

Hello, world - run 43

Hello, world - run 44

Hello, world - run 45

Hello, world - run 46

Hello, world - run 47

Hello, world - run 48

Hello, world - run 49

Hello, world - run 50

Types, formats and operators

There are other types we can use for our variables

bool: a Boolean expression of either true or falsechar: a single character like a or 2.- a single character always take up 1 byte of memory (8 bit).

double: a floating-point value with even more digitsfloat: a floating-point value, or real number with a decimal value- These are real numbers with a decimal point in them.

- Also contained within 4 bytes of memory (32 bits).

- It’s a little bit more complicated to talk about the value range of float. For float the limitation is with precision, hence the precision problem.

- Fortunately we have data type

doublewhich is double precision. It takes 8 bytes of memory (64 bits).

int: integers up to a certain size, or number of bitsintvalues are stored in 4 bytes so 32 bit. There are only 2&32 possible values.- limited to values ranging from negative 2^31 to positive 2^31.

- We also have unsigned int which is a qualifier that can be applied to int. It effectively doubles the positive range of variable of int with the cost of disallowing negative values. Therefore unsigned int values range from 0 to 2^32.

long: integers with more bits, so they can count higherstring: a string of charactersvoidis a type, but not a /data type/. It’s somewhat like a placeholder.structsare structures. These are defined types (/typedefs/) that are grouping of different data types. Defined types are custom data types.

And the CS50 library has corresponding functions to get input of various types:

get_charget_doubleget_floatget_intget_longget_string

For printf, too, there are different placeholders for each type:

%cfor chars%ffor floats, doubles%ifor ints%lifor longs%sfor strings

And there are some mathematical operators we can use:

+for addition-for subtraction*for multiplication/for division%for remainderWriting a function

The reason why we can use things like printf is that other people in the history of computer science has written up the function for us. We can do the same thing too.

In this example, lets’ write a custom function.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <cs50.h>

void cough(void)

{

printf("cough\n");

}

int main(void)

{

for (int i; i < 3; i++)

{

cough();

}

}

This is working code, however it does not look good. Why? Because it’s good practice to put the main function at the very top of our source code file. If we keep adding custom function to the top, we would have to scroll through millions of custom function declarations until we reach the main function when reading the source code.

If we simply move the main() declaration to the top, the compiler would spit out error? Why? Because at the time of main() being called, thus invoking cough(), the C compiler does not actually know what cough() is. This is because source code file are simply read top-down.

Here’s how we do it: We call the cough() earlier at the top, without actually specifying what it does.

#+begin_center c

#include

void cough(void);

int main(void) { for (int i; i < 3; i++) { cough(); } }

void cough(void) { printf(“cough\n”); } #+end_center

$ gcc function.c -o function -lcs50

$ ./function

cough

cough

cough

Memory, imprecision and overflow

Our computer has memory, in hardware chips called RAM, random-access memory. Our programs use that RAM to store data as they run, but that memory is finite. So with a finite number of bits, we can’t represent all possible numbers (of which there are an infinite number of). So our computer has a certain number of bits for each float and int, and has to round to the nearest decimal value at a certain point.

Let’s do a simple division:

x = 1

y = 10

print('%f'% (x/y))

- #+RESULTS:

- 0.100000

This is OK. However let’s try to see a bit further

x = 1

y = 10

print('%.50f'% (x/y))

- #+RESULTS:

- 0.10000000000000000555111512312578270211815834045410

This is called floating-point imprecision where we simply run out of bits to store all the possible float decimal values. Then the computer has to store the closest value it can to 1 divided by 10.

We face the same with integers that are too large, past a certain point:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void)

{

for (int i = 1;; i*=2)

{

printf("%i\n", i);

i*=2;

sleep(1);

}

}

$ gcc overflow.c -o overflow

$ ./overflow

1

4

16

64

256

1024

4096

16384

65536

262144

1048576

4194304

16777216

67108864

268435456

1073741824

0

0

0

0

This problem is called integer overflow where an integer can only be so big before the computer runs out of bits that can be used for a single integer and “rolls over”. When the roll over happen, as we have reached the cap for the number of bits, the carried 1 literally has no space to sit whereas all the other digits are turned into zero. This turns the whole integer into a zero.

Week 2 - Arrays

More about compiling

Compilation is the process of turning human-readable source code into machine code, or binary that our computers can understand and run it.

Compiling is actually made up of four small steps. These are:

- Preprocessing

This involves looking at lines that start with

#like,#includein C before everything else. Essentially, during pre-processing, these lines are replaced with other lines that are imported from the reference lirbraries, or header files. The new content is the lines that we want to include in our program. - Compiling

Even though we have been using this term quite liberally, its meaning is actually more precise than “turning source code into binary”. When a program is compiled, it is turned from source code into assembly code. They aren’t binary code however assembly codes are even lower-level instructions that are close to binary instructions that a computer’s CPU can understand. They generally operate on bytes themselves as opposed to abstractions like variable names. Assembly instructions are very low-level and the CPU follows these to move things around in its memory. It looks like this:

... main: # @main .cfi_startproc # BB#0: pushq %rbp .Ltmp0: .cfi_def_cfa_offset 16 .Ltmp1: .cfi_offset %rbp, -16 movq %rsp, %rbp .Ltmp2: .cfi_def_cfa_register %rbp subq $16, %rsp xorl %eax, %eax movl %eax, %edi movabsq $.L.str, %rsi movb $0, %al callq get_string movabsq $.L.str.1, %rdi movq %rax, -8(%rbp) movq -8(%rbp), %rsi movb $0, %al callq printf ... - Assembling

This is the step that involves turning the assembly code into zeroes and ones like

001111010101010. - Linking

This is the very last step of compilation where the contents of the previously compiled libraries that we want to link. For example when we put

#include <cs50.h>in our source code and then compile it, the compiledcs50.cmodule will be combined with the binary of our program so that the end product is a single binary file that includes instruction from our source code andcs50.c,stdio.c.

Bugs

Bugs are mistakes in programs that aren’t intentional. Debugging is the process of finding and fixing bugs.

For example, if we compile the following:

int main(void)

{

printf("hello, world\n");

}

We would get this error:

mistake.c: In function ‘main’:

mistake.c:3:5: warning: implicit declaration of function ‘printf’ [-Wimplicit-function-declaration]

3 | printf("hello, world\n");

| ^`

mistake.c:3:5: warning: incompatible implicit declaration of built-in function ‘printf’

mistake.c:1:1: note: include ‘<stdio.h>’ or provide a declaration of ‘printf’

+++ |+#include <stdio.h>

1 | int main(void)

This means that we have forgotten to include the #include <stdio.h> line at the beginning of our file. This library needs to be imported so that we can use printf.

The two above errors are syntax errors that are easily caught because they are thrown when we compile or run the program. However, we can also encounter logical errors that are trickier to catch. These are the ones that our programs will still run fine with, however it does not do exactly what we intend to instruct it to.

This is when debugger functionalities come in handy. Most IDEs offer these..

A core feature of amny IDE is to be able to add stop sign that instructs the IDE to stop at that line. This is what’s called a breakpoint. Essentially a breakpoint tells the computer that when we run our programe, don’t run it like usual. Instead stop there and allow us to step through the code step by step.

Data Types

Data types are different ways that we can store our variables in. Each of these take up a specific amount of computer space.

Memory

RAMs are chips we have inside our computers that store data for short-term use. This is why they are called ‘Random Access Memory’. We might save our programe or file to our hard drive or SSD for long-term storage, however when we open it, it gets copied to RAM first

Compared to long-term storage, RAM is smaller and more temporary and much faster.

We can think of bytes stored in RAMs as though they are in a grid, depicted in yellow in the image above. Therefore, if we instantiate a variable of type char, that variable will consume 4 bytes of the RAM.

Arrays

Ok Let’s say we want to store three variables in char.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

char c1 = 'H';

char c2 = 'I';

char c3 = '!';

printf("%c %c %c\n", c1, c2, c3);

}

When we compile and run this code, we should see H I !.

However, we learned in Week 0 that characters are really just numbers underneath before they get translated using ASCII. So we can change the print format in our program to the below in order to see the numeric values of each char ( H I !) which are ( 72 73 33).

// Prints ASCII codes

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

char c1 = 'H';

char c2 = 'I';

char c3 = '!';

printf("%i %i %i\n", c1, c2, c3);

}

When we do something like this, in our computer memory, we may have three boxes labeled c1 , c2, c3 that store these variables when they are called, although in the computer’s brain, down to the super low level, they would not be 72, 73 or 33 but just zeroes and ones.

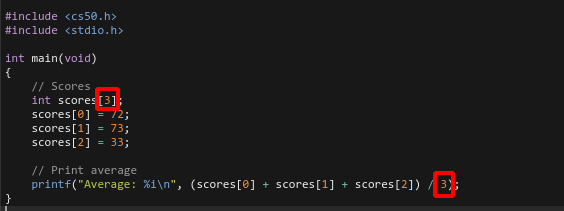

Suppose we have a script to calculate the average of three number:

// Averages three numbers

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

// Scores

int score1 = 72;

int score2 = 73;

int score3 = 33;

// Print average

printf("Average: %i\n", (score1 + score2 + score3) / 3);

}

This is not really the best design. By design this program only accepts three variable so it is not very usable especially with the intended use case of recording class scores.

In C, if we know that we’ll be storing more than one variables of the same type, we can use an array. An array is a list of value that can store multiple variables together.

In C, we can instantiate an array of integers like this:

// Averages three numbers using an array

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

// Scores

int scores[3];

scores[0] = 72;

scores[1] = 73;

scores[2] = 33;

// Print average

printf("Average: %i\n", (scores[0] + scores[1] + scores[2]) / 3);

}

Arrays are zero index.

What does the number three [3]? It represents the number of values that are reserved for a single variable. This is still a limitation of this program.

The above code also violates the DRY principle which is “Don’t Repeat Yourself”. The Repetition is here:

So, the next iteration of the same function could be:

// Averages three numbers using an array and a constant

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

const int N = 3;

int main(void)

{

// Scores

int scores[N];

scores[0] = 72;

scores[1] = 73;

scores[2] = 33;

// Print average

printf("Average: %i\n", (scores[0] + scores[1] + scores[2]) / N);

}

In the above program, the constant N is actually a global variable. Using global variables is normally considered bad practice however it’s OK in places where we use constants.

The next iteration of this program would be below, where the number of scores can be dynamic, depending on the user.

// Averages numbers using a helper function

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

float average(int length, int array[]);

int main(void)

{

// Get number of scores

int n = get_int("Scores: ");

// Get scores

int scores[n];

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

scores[i] = get_int("Score %i: ", i + 1);

}

// Print average

printf("Average: %.1f\n", average(n, scores));

}

float average(int length, int array[])

{

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++)

{

sum += array[i];

}

return (float) sum / (float) length;

}

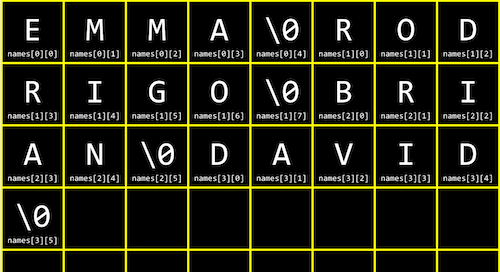

Strings

Strings are actually just arrays of characters (char). We can also just access individual char within a string just like how we would access a member of an array.

There is one special thing about a string and that is the lack of any preordained length associated with each of them. Any char can only take 1 bytes however a string can essentially be infinitely long.

In C, a string ends with a special terminating character \0. This is essentially to mark the end of a string variable in the computer’s memory space.

The two printf() statements below prints the same content: EMMA.

string names[4];

names[0] = "EMMA";

names[1] = "RODRIGO";

names[2] = "BRIAN";

names[3] = "DAVID";

printf("%s\n", names[0]);

printf("%c%c%c%c\n", names[0][0], names[0][1], names[0][2], names[0][3]);

In the above example we have initialized four string variables. Although there is no concept of left-right, up-down in a computer memory space, we can think of it like the representation below:

This is not what programming is. However it’s good to know what’s going on under the hood, which is just manipulation of data.

Going low-level under the hood

Although we may not need to do this particular task, it would be good to know how the standard uppercase() functions work.

If we look at an ASCII translation table, we will learn the the ASCII code of A is 65, a is 97, B is 66, b is 98` and so on.. We also know that under the hood, characters are essentially just integers that are translated by the computes using ASCII translation which is made by human.

Therefore, let’s say we want to make a function that can be used to print all inputs in uppercase, this is how we would do it. This is also how this function is programmed under the hood.

// Uppercases a string

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

string s = get_string("Before: ");

printf("After: ");

for (int i = 0, n = strlen(s); i < n; i++)

{

if (s[i] >= 'a' && s[i] <= 'z')

{

printf("%c", s[i] - 32);

}

else

{

printf("%c", s[i]);

}

}

printf("\n");

}

Of course, we shouldn’t really be programming these low-level functions. In C, we should be using the ctype.h library which contains toupper() function to do this sort of thing, i.e:

// Uppercases string using ctype library (and an unnecessary condition)

#include <cs50.h>

#include <ctype.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

string s = get_string("Before: ");

printf("After: ");

for (int i = 0, n = strlen(s); i < n; i++)

{

if (islower(s[i]))

{

printf("%c", toupper(s[i]));

}

else

{

printf("%c", s[i]);

}

}

printf("\n");

}

Command-line arguments

We can write our program to accept command-line arguments which are just additional words after the name of our program. In c, we can do it like this:

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, string argv[])

{

if (argc == 2)

{

printf("hello, %s\n", argv[1]);

}

else

{

printf("hello, world\n");

}

}

The way that command line arguments work is that the extra words that come after our program’s name in the terminal are stored in an array as well and can be accessed within our code.

In C, arc is the argument count and argv is an array of string that are the arguments. In argv, the very first argument is the name of the program being executed.

This program below checks if there is one argument that is passed, if not the program would exit with failure.

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, string argv[])

{

if (argc != 2)

{

printf("missing command-line argument\n");

return 1;

}

printf("hello, %s\n", argv[1]);

return 0;

}

In programming, a successfully executed program would return with a status code equal 0 . For unsucessful termination, we can use whatever, however let’s keep it simple and use 1.

Week 3 - Algorithms

Although a computer is very powerful, in a way it is quite limited. When we think about memory in a computer, or RAM, data is stored as individual variables or as arrays of many items. This can be thought of like rows of lockers where the computer can only open one locker to look at an item, one at a time.

A computer can’t look at all the elements and take it all in.

Let’s now consider a very basic problem, where we want to check whether a number is in an array. We need an algorithm that took in an array as input and produce a boolean as a result.

A linear search would look like this. A linear search is basically looking in each locker one at a time from the beginning to the end.

For i from 0 to n-1

if i'th element equals X

return True

return false

A binary search would look this. It is basically to start in the middle and move left or right depending on what we are looking for, if our array is sorted.

If no items

return False

If middle item is 50

return True

Else if 50 < middle item

search left half

Else if 50 > middle item

search right half

Big O

The graph above illustrates different algorithms with the big /O/ notation, which can be thought of as “on the order of”. Big /O/ notation represent the upper bound of the number of steps for our algorithm.

In the graph, the straight lines describes a linear algorithm. We refer to them as the number of steps that might need to be taken in the worse case scenario. For example, considering the line representing O(n), which is “on the order of n”, if we have 7 lockers and we need to find one that contains something we look for, in the worst case scenario that we apply a linear algorithm, it would take 7 steps.

Similarly, a logarithmic running time is O(log n), no matter what the base is, since this is just an approximation of what happens with n is very large.

Some computer scientists might also use the big Ω notation, or big /Omega/ notation which is the lower bound of number of steps for our algorithm, or the best case scenario. For a linear algorithm, the best case scenario would be 1 step.