Go by Example

Today I am starting to learn Go Lang at https://gobyexample.com/.

Go - General

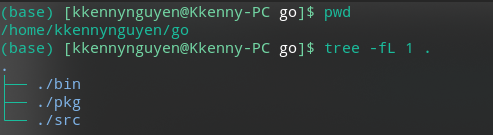

Go Workspace

Go programmers normally put all their source codes in a Go code in a single workspace including other packages and dependencies that are installed.

The workspace is normally located within the $USER directory. The workspace folder should have the main ~src~ folder that contain ~.go~ code files and also a ~bin~ folder that contains the executable commands. There is also a ~pkg~ folder that contains installed third-party packages.

This is how a Go workspace is structured:

Package Management in Go

The concept of packages is quite familiar for Java, Javascript or Node programmer. A package is nothing but a directory with some code files, which exposes different variables (features) from a single point of reference.

Example: You are working on project with more than a thousand functions that you constantly need to call. Some of these functions have similar behaviours or target the same input type. For example ~toUpperCase()~ and ~toLowerCase()~ both transform case of a ~string~, so we would put both of these functions together in one code file named /case.go/. We also have other functions that operates on ~string~ data so we would also write them in seperate code file under the same directory /string//. We would also have other directory that reside on the same level as /string//, which all live under a parent directory.

package-name

├── string

| ├── case.go

| ├── trim.go

| └── misc.go

└── number

├── arithmetics.go

└── primes.go

In the above example, /string/ and /number/ are different packages.

In Go, every program must be a part of some package. A stand-alone executable Go program must have ~package main~ declaration at the beginning of the file. This is the entry point of any Go program.

Running a non-main package would return: ~cannot run non-main package~ error.

A complete program is created by linking a single, unimported package called the /main package/ with all the packages that it imports, transitively. The main package must have package name ~main~ and declare a function ~main~ that takes no arguments and returns no value: ~func main() {…}~. Program execution the begins by initializing the main package and then invoking the function ~main~. When that function invocation returns, the program exits. It does not wait for other non-main go-routines to complete.

If a program is part of the main package, then ~go install~ will create a binary file, which upon execution calls ~main~ function of the program. If a program is part of a package other than ~main~, then a ~package archive~ file is created with ~go install~ command.

When we run ~go install [app]~ command, Go will look for the ~[app]~ sub-directory inside the ~src~ directory of ~GOPATH~, if ~GOROOT~ doesn’t have it. If it finds the ~[app]~ subdir, Go will then compile the package and create a ~[app]~ binary executable file inside the ~bin~ directory, which is set by ~GOBIN~.

~go install

There are two types of packages. An executable package and a utility package. An executable pacakge is our main application since we will be running it. A utility package is not self-executable, instead it enhances the functionality of an executable package by providing utility functions and other important assets.

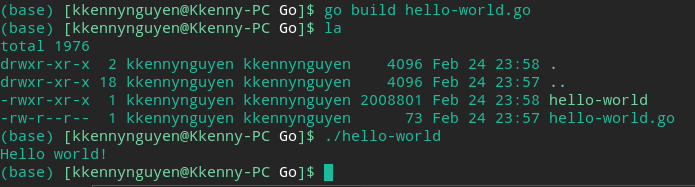

Hello World

A classic programming course always starts with a ‘Hello World’ message.

In go, the, this can be done by the following:

/File name: hello-world.go/

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello world!")

}

To run the program we can use ~go run~.

$ go run hello-world.go

Hello world!

Sometimes we need to build the programs into binaries. This can be done by ~go build~.

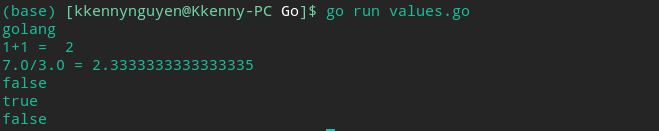

Values

Similarly to other languages, Go also has various value types including strings, integers, floats, booleans, etc.. These data types can also be used with operators that you’d normally expect.

/values.go/

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("go" + "lang")

fmt.Println("1+1 =", 1+1)

fmt.Println("7.0/3.0 =", 7.0/3.0)

fmt.Println(true && false)

fmt.Println(true || false)

fmt.Println(!true)

}

Variables

A variable is a storage unit of a particular data type.

In Go, variables are explicitly declared and used by the compiler. Variables are created by first using the ~var~ keyword then specifying the variable name (~x~). the type (~string~) and finally an initialized value (~Hello World~). The last step is optional.

var x string = "Hello World"

We can also do:

var x string

x = "first"

Which means:

- x string is a new variable

- x takes the string Hello World

~var~ declares one or more variables. Go will infer the type of initialized variables. Variables declared without a corresponding initialization are /zero-valued/, e.g the zero value for an int is 0.

We can also use the short-hand syntax to declare and initializing variable: ~:=~:

x := "Hello World"

The type is not necessary because Go compiler is able to infer the type of variable based on the literal value that has been assigned (“Hello World”).

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declare a string

var a = "initial"

fmt.Println(a)

// Work with integer and multiple variable assignment

var b, c int = 1, 2

fmt.Println(b, c)

fmt.Println(b + c)

// Work with bool

// Note 'true' not 'True

var d = true

fmt.Println(d)

// No literal value, default = 0

var e int

fmt.Println(e)

// short-hand

f := "apple"

fmt.Println(f)

}

- #+RESULTS:

- initial

- 1 2

- 3

- true

- 0

- apple

Constants

Go support constants of the following data types: character, string, boolean, numeric.

Some languages don’t have constants. Constant is a variable in Go with a fixed value. Any attempt to change the value of a constant will cause run-time panic.

To declare a constant value, use ~const~. A ~const~ statement can appear anywhere a ~var~ statement can. Constants cannot be declared using ~:=~ syntax.

Constant expressions perform arithmetic with arbitrary precision.

A numeric constant has no type until it’s given one, such as by an explicit conversion.

A number can be given a type by using it in a context that requires one, such as a variable assignment or a function call. For example, ~math.Sin(x)~ expects x to be a ~float64~.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

const s string = "constant"

func main() {

fmt.Println(s)

const n = 50000000000

const d = 3e20/n

fmt.Println(d)

fmt.Println(int64(d))

fmt.Println(math.Sin(n))

}

- #+RESULTS:

- constant

- 6e+09

- 6000000000

- -0.5608712390143394

For

~for~ is Go’s only looping construct. Go does not have ~while~.

This is the most basic type of ~for~ loop in Go, with a single condition:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 1

for i <= 10 {

fmt.Println(i)

i = i + 1

}

}

#+RESULTS: #+begin_example 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 #+end_example

The above program could also be written like this, which is the classic initial/condition/after for loop declaration:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := 1; i <= 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}

#+RESULTS: #+begin_example 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 #+end_example

~for~ without a condition will loop repeatedly until you ~break~ out or ~return~ from the enclosing function. We can also do ~continue~ to the next iteration of the loop.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 1

for i <= 3 {

fmt.Println(i)

i +=1

}

for j := 7; j <= 9; j++ {

fmt.Println(j)

}

for {

fmt.Println("loop")

break

}

for n := 0; n <= 5; n ++ {

if n %2 == 0 {

continue

}

fmt.Println(n)

}

}

#+RESULTS: #+begin_example 1 2 3 7 8 9 loop 1 3 5 #+end_example

Five basic ~for~ loop patterns

Three-component loop

This is the basic loop. It contains three components: - The init statement, e.g ~i := 1~. - The condition, e.g ~i < 5~, is computed. - If true, the loop body runs. The scope of ~i~ is limited to the loop. - Otherwise, the loop is done. - The post statement, e.g ~i++, runs.~ - Back to step 2, i.e checking if condition is stil true

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 0

for i := 1; i < 5; i++ {

sum +=i

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}

- #+RESULTS:

- 10

While loop

Although Go doesn’t a ~while~ statement, if we skip the init and the post statements, we get a while loop.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

n := 1

for n < 5 {

n *= 2

}

fmt.Println(n) // 1*2*2*2

}

- #+RESULTS:

- 8

Infinite loop

If we also skip the condition, we have an infite loop. The following program will never finish computing:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 0

for {

sum++

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}

For-each range loop

Looping over elements in slices, arrays, maps, channels or strings is often best done with a range loop.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

strings := []string{"hello", "world"}

fmt.Println(strings)

for i, s := range strings {

fmt.Println(i, s)

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- [hello world]

- 0 hello

- 1 world

- The range expression, ~strings~ is evaluated once before beginning of the loop.

- The iteration values are assigned to the respective iteration variables, ~i~ and ~s~, as in an assignment statement.

- The second iteration variable is optional (~s~).

- For a nil slice, the number of iterations is 0.

String iteration

You can also do string iteration: runes or bytes.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i, ch := range "日本語" {

fmt.Printf("%#U starts at byte position %d\n", ch, i)

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- U+65E5 ‘日’ starts at byte position 0

- U+672C ‘本’ starts at byte position 3

- U+8A9E ‘語’ starts at byte position 6

- The index is the first byte of a UTF-8-encoded code point; the second value, of type ~rune~ is the value of the code point.

- For an invalid UTF-8 sequence, the second value will be 0xFFFD, and the iteration will advance a single byte.

To loop over individual bytes, we can simply use a normal for loop and string indexing:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

const s = "日本語"

for i := 0; i < len(s); i++ {

fmt.Printf("%x ", s[i])

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- e6 97 a5 e6 9c ac e8 aa 9e

Map iterations: key and values

```go package main

import “fmt”

func main() { m := map[string]int{ “one”: 1, “two”: 2, “three”: 3, } for k, v := range m { fmt.Println(k, v) } } ```

#+RESULTS:

: three 3

: one 1

: two 2

Note: The iteration order over maps is not specified and is not guaranteed to be the same order from one iteration to another, i.e if we re-run the above program it may print the key:value pair in a different order.

Exit a loop

The ~break~ and ~continue~ keywords work just as they do in C and Java.

| ~continue~ = skip | begins the next iteration of the innermost ~for~ loop at its post statement |

| ~break~ = stop | leaves the innermost ~for~, ~switch~ or ~select~ statement. |

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 0

for i := 1; i < 5; i++ {

if i%2 != 0 {

// skip odd number

continue

}

sum += i

}

fmt.Println(sum) // should be 2 + 4

}

- #+RESULTS:

- 6

If/ Else

In Go, branching with ~if~ and ~else~ is straight-forward.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

if 7%2 == 0 {

fmt.Println("7 is even")

} else {

fmt.Println("7 is odd")

}

if num := 9; num < 0 {

fmt.Println(num, "is negative")

} else if num < 10 {

fmt.Println(num, "has 1 digit")

} else {

fmt.Println(num, "has multiple digit")

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- 7 is odd

- 9 has 1 digit

In Go, we don’t need parentheses around conditions. However the braces are required.

Switch

~switch~ statements express conditionals across many branches.

We can use commas to separate multiple expressions in the same ~case~ statement. We can also use the optional ~default~ case.

Instead of doing this:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 1

if i == 0 {

fmt.Println("Zero")

} else if i == 1 {

fmt.Println("One")

} else if i == 2 {

fmt.Println("Two")

} else if i == 3 {

fmt.Println("Three")

} else if i == 4 {

fmt.Println("Four")

} else if i == 5 {

fmt.Println("Five")

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- One

We can use the ~switch~ statement. A ~switch~ statement starts with the keyword ~switch~, followed by an expression - in this case ~i~ and then a series of ~case~. The value of the expression is compared to the expression following each ~case~ keyword. If the value and the keyword are equivalent, then the statement following the ~:~ is executed. Similarly to the ~if~ statement, each case is checked top down and the first one to succeed is chosen.

~case~ statement also have a ~default~ case which will happen if none of the cases matches the value.

Instead of doing the ~if~ statements above, we can do:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 1

switch i {

case 0:

fmt.Println("Zero")

case 1:

fmt.Println("One")

case 2:

fmt.Println("Two")

case 3:

fmt.Println("Three")

case 4:

fmt.Println("Four")

case 5:

fmt.Println("Five")

default:

fmt.Println("Unknown number")

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- One

.. to use the ~default~ statement:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 7

switch i {

case 0:

fmt.Println("Zero")

case 1:

fmt.Println("One")

case 2:

fmt.Println("Two")

case 3:

fmt.Println("Three")

case 4:

fmt.Println("Four")

case 5:

fmt.Println("Five")

default:

fmt.Println("Unknown number")

}

}

- #+RESULTS:

- Unknown number

You can also use ~switch~ without an expression. It is an alternate way to express if/else logic.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

i := 2

fmt.Print("Write ", i, " as ")

switch i {

case 1:

fmt.Println("one")

case 2:

fmt.Println("two")

case 3:

fmt.Println("three")

}

switch time.Now().Weekday() {

case time.Saturday, time.Sunday:

fmt.Print(" Today is ", time.Now().Weekday(), ".It's the weekend! \n")

default:

fmt.Print("Oh mann It's only ", time.Now().Weekday(), ".\n")

}

t := time.Now()

// switch without expression

switch {

case t.Hour() < 12:

fmt.Println("Good morning!")

default:

fmt.Println("It's after noon!")

}

/*

A type switch can be used to compare types instead of values.

This can be used to discover the type of an interface value.

*/

whatAmI := func(i interface{}) {

switch t := i.(type) {

case bool:

fmt.Println("I'm a bool.")

case int:

fmt.Println("I'm an integer.")

default:

fmt.Printf("Don't know type %T\n", t)

}

}

whatAmI(true)

whatAmI(1)

whatAmI("hey")

whatAmI(0.6)

}

- #+RESULTS:

- Write 2 as two

- Oh mann It’s only Wednesday.

- It’s after noon!

- I’m a bool.

- I’m an integer.

- Don’t know type string

- Don’t know type float64

Arrays

An array is a numbered sequence of elements of a single type with a fixed length. In Go they look like this:

var x [5]int

~x~ is an example of an array which is composed of 5 ~int~

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var x [5]int

x[4] = 100

fmt.Println(x)

fmt.Println(x[4])

}

- #+RESULTS:

- [0 0 0 0 100]

- 100

The statement ~x[4] = 100~ can be read as “set the 5th element of the array x to 100”. In Go, similar to Python, arrays are indexed starting from 0.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Create an array that holds exactly 5 ints

// By default, an array is zero valued.

var a [5]int

fmt.Println("emp:", a)

a[4] = 100

fmt.Println("set:", a)

fmt.Println("get:", a[4])

// Shorter syntax for array

b := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

fmt.Println("dcl:", b)

// multi-dimensional array

var twoD [2][3]int

fmt.Println(twoD)

for i := 0; i < 2; i++ {

for j := 0; j < 3; j++ {

twoD[i][j] = i + j

}

}

fmt.Println("2d:", twoD)

}

- #+RESULTS:

- emp: [0 0 0 0 0]

- set: [0 0 0 0 100]

- get: 100

- dcl: [1 2 3 4 5]

- [[0 0 0] [0 0 0]]

- 2d: [[0 1 2] [1 2 3]]

An example of program that uses array to compute the average test score:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var score [5]float64

score[0] = 56

score[1] = 65

score[2] = 87

score[3] = 90

score[4] = 28

var total float64

for i := 0; i < len(score); i++ {

total += score[i]

}

fmt.Println("total:", total)

fmt.Println("avg:", total/float64(len(score))) // We have to convert len(score) into a float64

}

- #+RESULTS:

- total: 326

- avg: 65.2

We can also use a special form of the ~for~ loop:

In this loop, ~i~ represents the current positio and ~value~ is the same as ~score[i]~. We use the keyword ~range~ followed by the name of the variable we want to loop over.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var score [5]float64

score[0] = 56

score[1] = 65

score[2] = 87

score[3] = 90

score[4] = 28

var total float64

for i, value := range score {

total += value

}

fmt.Println("total:", total)

fmt.Println("avg:", total/float64(len(score))) // We have to convert len(score) into a float64

}

command-line-arguments

/tmp/babel-SPIxT5/go-src-b7Uuux.go:16:6: i declared but not used

The reason we go the error is that Go compiler does not allow us to create variables that are never used. As we don’t use ~i~ insire of our loop, we need to change it to the underscore ~~. An underscore (~~) is used to tell the compiler that we don’t need the variable.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var score [5]float64

score[0] = 56

score[1] = 65

score[2] = 87

score[3] = 90

score[4] = 28

var total float64

for _, value := range score {

total += value

}

fmt.Println("total:", total)

fmt.Println("avg:", total/float64(len(score))) // We have to convert len(score) into a float64

}

- #+RESULTS:

- total: 326

- avg: 65.2

#Slices#

Slices are a key data type in Go. Slices give a more powerful interface to sequences than array.

In Go, the slice type is abstraction built on top of array type. Arrays are inflexible and don’t get used a lot in Go code. Slices, however, are everywhere. They build on arrays to provide great power and convenience.

A slice is a segment of an array. Like arrays slices are indexable and have a length. Unlike arrays the length is allowed to change. Here’s an example of a slice ~var x []float64~. Unlike arrays, slices are typed only by the elements they contain, not the number of elements.

~len()~ returns the length of the slice as expected.

The only difference between an array and a slice is the missing length between the brackets. In the above example, ~x~ has been created with a length of ~0~.

We should create a slice using the built-in ~make~ function: ~x := make([]float64, 5)~. This creates a slice that is associated with an underlying ~float64~ array of length 5. Slices are always associated with an underlying array, although they can never be longer than the array, they can be smaller.

A slice is a descriptor of an array segment. It consists of a pointer to the array, the length of the segment and its capacity (maximum length of the segment).

In addition to the basic operations, slices support several more that make them richer than arrays. One is the built-in ~append~ which returns a slice containing or or more new values. Note that we need to accept a return value from ~append~ as we may get a new slice value.

Slices can also be copy’d.

Slices support a slice operator with the syntax ~slice[low: high]~.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// create a slice of strings of length 3

s := make([]string, 3)

fmt.Println("emp:", s)

s[0] = "a"

s[1] = "b"

s[2] = "c"

fmt.Println(s)

fmt.Println(s[2])

fmt.Println("len", len(s))

// appending

s = append(s, "d")

s = append(s, "e", "f")

fmt.Println("appended:", s)

// create an empty slice c

c := make([]string, len(s))

// copy c from s

copy(c, s)

fmt.Println("copy:", c)

// slice operator

// slice from and inclduing 2 upto and excluding 5

l := s[2:5]

fmt.Println("from 2 to 5:", l)

// slice from and including 2

n := s[2:]

fmt.Println("from 2:", n)

// Declare and initialize a variable for slice in a single line

t := []string{"hello", "world"}

fmt.Println("dcl:", t)

// Slices can also be composed into multi-dimensional data structures.

// The length of the inner slices can vary, unlike with multi-dimensional arrays

// Create a twoD slice with outer length = 3, inner length can vary

twoD := make([][]int, 3)

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

innerLen := i + 1

twoD[i] = make([]int, innerLen)

for j := 0; j < innerLen; j++ {

twoD[i][j] = i + j

}

}

fmt.Println("2d:", twoD)

}

#+RESULTS: #+begin_example emp: [ ] [a b c] c len 3 appended: [a b c d e f] copy: [a b c d e f] from 2 to 5: [c d e] from 2: [c d e f] dcl: [hello world] 2d: [[0] [1 2] [2 3 4]] #+end_example

Maps

Maps are Go’s built-in associative data type. This is called dict or hashes in other languages.

To create an empty map, we need to use the built in ~make~ statement in this format: ~make(map[key-type]value-type)~

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// create an empty map

// make(map[key-type]value-type)

m := make(map[string]int)

m["k1"] = 7

m["k2"] = 13

fmt.Println("map:", m)

// Get a value for a key using name[key]

fmt.Println("key 1:", m["k1"])

// Print the number of key/value pairs

fmt.Println("lenth:", len(m))

// Delete a key from the map

delete(m, "k2")

fmt.Println("After delete:", m)

// This key doesn't exist, so the return value is 0

prs := m["k2"]

fmt.Println("prs:", prs)

/* Use optional second return value when getting a value from a map.

This helps indicate if they key was present in the map and return a bool value.

It can be used to disambiguate between missing keys and keys with 0 value or "".

i.e the second optional return value will be false.

*/

prs, prs1 := m["k2"]

fmt.Println("prs:", prs, "prs1:", prs1)

// If we don't need the return value, we can just use "_" and get the second value only

_, o2o := m["k2"]

fmt.Println("optional 2nd value only:", o2o)

}

- #+RESULTS:

- map: map[k1:7 k2:13]

- key 1: 7

- lenth: 2

- After delete: map[k1:7]

- prs: 0

- prs: 0 prs1: false

- optional 2nd value only: false